Designing unrest

Issue: XXIX.2 March - April 2022Page: 20

Digital Citation

Authors:

Tom Bieling, Frieder Bohaumilitzky, Anke Haarmann, Torben Körschkes

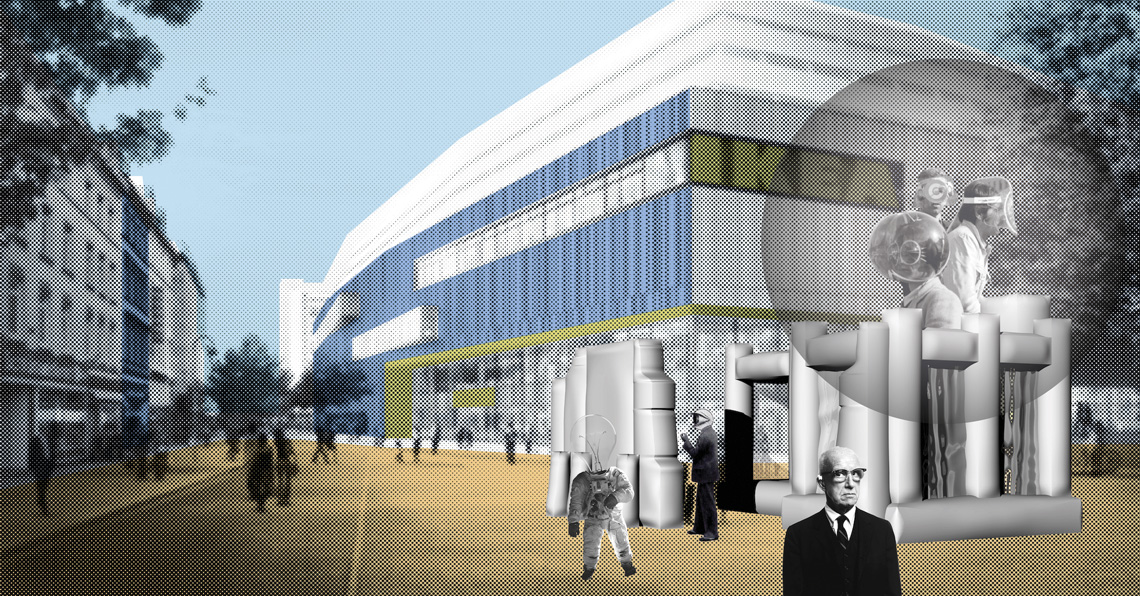

The shaping of our world is an ongoing process of negotiation and dissent, a state of perpetual unrest. How do we—as designers, as a society—move in and through (spaces of) unrest? A starting point for this question is the project Metapolitisches Hüpfen (Metapolitical Bouncing; Figure 1) by Frieder Bohaumilitzky, who turned Hambach Castle into a bouncy castle. Hambach Castle is a historical symbol for the German democracy movement. But it is also currently used as a backdrop for right-wing events. As a materialized metaphor, the castle symbolizes the observation that a society's self-image is both negotiated by and performed in symbolic spaces. In order to create a space in which effective strategies against right-wing metapolitics can be designed and tested, the bouncy castle attempts to bring unrest into the staging of these self-understandings.

|

Figure 1. Metapolitisches Hüpfen by Frieder Bohaumilitzky, 2021. Funded by the Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg, Behörde für Kultur und Medien. The collage includes found footage. |

It can be argued that every political system forms an interwoven relationship with design systems. Democracy is no exception. Unlike some other political systems, however, a democratic society is hardly conceivable without a public sphere that encompasses multiple, constantly negotiated everydays—dissent is essential in keeping it alive. Design plays an important role in this social fabric by influencing, motivating, or even preventing social forms of behavior through its artifacts and settings. Design influences the form(s) in which a society arranges its coexistence. That is to say, it affects whether negotiations take place and are carried out in purely symbolic spaces or whether design itself is understood as an actor in spaces of societal friction. Perhaps it is a central task for designers to focus on such concrete conflicts and controversies. This would also mean making a significant contribution to ensuring that democracy not only functions as a structure and a symbol but also remains a process that provokes and requires practical conflicts and positional disputes, as well as providing an epistemic representation (e.g., visual, material, informative) of both.

The concept of unrest can be considered in two ways: as a counter-proposal to an understanding of democracy as a purely formal and symbolic structure, and as a response to the rigid practices of knowledge production. Do we need to design unrest to undermine the incrustation and ideologization of democracy and knowledge production? What epistemological or theoretical tools and what instruments of design do we have at our disposal? What dispositives can we—as designers, artists, philosophers, and social scientists—make available without these in turn becoming rigidly fixed, predetermined?

To provoke dissent and bring unrest to the cause of democratic and epistemic self-understanding, we continue to use the figure of the bouncy castle in our research project Speculative Space and in other settings. "Bouncing" (Figure 2) in the bouncy castle serves as both a metaphor and a practice for breaking out of rigid knowledge productions and modes of enactment. In the context of our lecture performance Design of Unrest (Figure 3) at the symposium "Attending [To] Futures," the bouncy castle presents itself as a deliberately wobbly materialized invitation to bring unrest into knowledge and entrenched thinking practices: Childlike bouncing undermines adult (academic) epistemological seriousness. Knowledge takes off, falls off balance, and when it lands back down again, it finds itself off keel, displaced (Figure 4).

Design of Unrest is an attempt to develop an understanding of places as places of knowledge, of spaces as spaces of negotiation, of things as things of meaning. As technology has infiltrated the world in which we live, societal development takes place with and through these places and things. This circumstance alone already defines a space for political intervention.

Tom Bieling is a postdoc at ZfD Zentrum für Designforschung (HAW Hamburg), chief editor at Designforschung.org, a member of the Board of International Research in Design (BIRD), and co-editor of Design Meanings. He was a research associate at UdK Berlin (2010–2019) and TU Berlin (2007–2010). His recent books include Design (&) Activism, Inklusion als Entwurf, and Gender (&) Design. [email protected] www.tombieling.com

Frieder Bohaumilitzky is a Ph.D. candidate at the HFBK Hamburg and a research associate at the Zentrum für Designforschung at HAW Hamburg. He studied political science at the Universität Hamburg and design at the HFBK Hamburg and the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design Jerusalem. He examines the relationship between design, right-wing populism, and right-wing extremism. [email protected] www.bohaumilitzky.de

Anke Haarmann works at the intersections of philosophy, visual arts, curatorial practice, and design theory. Her thematic focuses are artistic research and design research as well as the theory and practice of public and urban space. Haarmann has a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Potsdam, was a postdoc at Leuphana University Lüneburg, and currently is a professor of design theory and design research at HAW Hamburg, where she established and heads the Centre for Design Research. [email protected]

Torben Körschkes is doing his Ph.D. on chaotic arrangements and detotalized communities at TU Berlin and works as a research associate at the Centre for Design Research at HAW Hamburg. He is part of the design and research collective HEFT, which works on questions of sociopolitical spaces and negotiation practices. He studied industrial design at Folkwang UdK in Essen and experimental design at HFBK Hamburg. [email protected]

Copyright held by authors

The Digital Library is published by the Association for Computing Machinery. Copyright © 2022 ACM, Inc.

![Still from the film premiered at the symposium "Attending [To] Futures. Questions of Politics in Design, Education, Research, Practice."](https://dl.acm.org/cms/attachment/9b7b578c-f8c0-49e1-84f9-36eb4c06eb87/ins03.gif)