Authors: Yvonne Rogers

Posted: Thu, May 28, 2020 - 1:46:39

Covid-19 forced governments to urge full or partial lockdown measures to slow the progression of the pandemic. By the end of March, more than 100 countries had “locked down” billions of people. During that time, Yvonne Rogers wrote a series of blog posts on the topic of “remote,” structured around the themes of living, working, numbers, and tracking (the full articles and more posts are available on her website: https://www.interactiveingredients.com). She asks: Is remote the new normal? As we contemplate when we will all meet again face-to-face, Rogers helps us reflect on what remote means now for living and working, while also considering fresh ideas on how we plan to slow the pandemic with technology and save lives.

Remote working: March 19, 2020

Since March 12, 2020, we have been working remotely, as the university instructed us to do because of the escalation of coronavirus. It feels like I have had more videoconferencing meetings than hot dinners! One moment it is Skype, the next Teams, then Zoom—many have been back-to-back. Even though it is great that we can keep in touch in this virtual way, it is frankly exhausting—but in a different way from a usual tiring day at work. While my twice-daily train commute takes a toll, being glued to a screen for hours on end, talking to virtual colleagues and students elevates fatigue to a new dimension. The exhaustion is less physical than it is enervating, like after a long Sunday of too much binge watching.

This phenomenon has since been dubbed Zoom fatigue. Part of the new tiredness stems from meetings that differ greatly from the usual—dealing with so many updates each day on what has been planned, decided, revealed, or mandated by government, university, or university department. Right now, an awful lot of “cascading” is interspersed with checking up on and reassuring each other. There seems to be much less actual work, but one hopes this will shift once routines begin to settle into place.

Then, out of the blue, you might get an email from one of your colleagues letting you know they are not feeling well and have begun self-isolating. It is quite anxiety-inducing, worrying if they have contracted Covid-19. I have heard now from quite a few people that they have developed flu-like symptoms and are self-isolating; some situations seem more serious than others. It is all a bit discombobulating, like Russian roulette. You can but hope they will be better the next day.

Today it was raining, so we put our umbrellas up, making it easier for us to social distance. At one point I entered a shop, and while waiting in line, other customers came in and stood two meters apart from us and each other, abiding by government guidance. It felt a little strange and silly as we carefully navigated the small place. But even though it seemed unnatural, it felt prudent.

Later in the morning, when I peered out of my study window that looks onto a primary school playground, I saw many 5- and 6-year-old children playing together during their break time without a care in the world (as it happens, it was probably the last time for a while; U.K. schools closed soon after). For them, the concept of social distancing must seem alien. As for taking part in social isolation, it must seem even stranger: Why can’t we go out to play? Why must we stay indoors without physical contact with our grandparents or playmates?

This new world order brings out the best and worst in people. There are so many acts of kindness being reported that it makes you feel warm and fuzzy, realizing that, as human beings, we like to look out for each other. However, the flipside is just how many people are looking out for themselves. Many can’t resist the temptation to stock up on tins, bread, toilet paper, and other staples. Panic buying maybe, but it gives them something to do and makes them feel safe. I found myself today, after failing to find any cereal left on the shelves, wondering if I should buy the last remaining cereal bar that I spotted. I would never normally buy such a thing, let alone eat it. But self-restraint is tough when irrational fears enter our psyche. As it turned out, one of my neighbors came to the rescue and brought around a tasty loaf of bread.

We have all started to sign off on emails with “Stay safe.”

Remote living: March 25, 2020

So the official lockdown kicked in on Monday, March 23, 2020, for those of us living in the U.K. The rules are a bit more lenient than in some countries, where they have draconian curfew measures in place. Here, we are allowed to leave home for one exercise session a day, and to go shopping to buy necessary food and medicine. We are also allowed to go to work if we absolutely can’t work from home. So for the time being, if you are a construction worker, you can carry on as normal—as long as you social distance. It seems like a good time to be a crane operator, high in the sky looking down on empty streets. I suspect not for long. It must be very difficult for a government to balance its country’s economic needs against how best to flatten the pandemic curve—all while determining how to change human behavior into something so very different from how people normally live their lives.

Yesterday I did my beach walk alone at 8 a.m. to start the day. There were many joggers and dog walkers. There was also plenty of space, so we managed to keep our distance. The sea looked calm and serene, and for that hour I could think of something other than coronavirus. Today I am saving up my permitted outside exercise for later in the day. By midafternoon yesterday, I was getting quite restless. At one point I looked at my watch thinking it was 4:15 p.m.—nearly time for a planned chat with a friend—only to discover it was actually 3:15. Normally, being surprised by finding I have an extra hour would be a joy. I can easily fill it in by catching up on work. This time, I can honestly say my heart sank a little, reminding me of when I was a teenager on a long Sunday when the clock stood still…

Meanwhile, all around us is a flurry of activity online. I see that lovely Amanda is streaming her yoga class to us at UCL on Friday at work. A couple just got married in Birmingham, before the country banned weddings; over 100 guests watched it being livestreamed on Facebook. There are also sweet videos of grandchildren now doing the rounds, waving at their grandparents through the windows or patio doors in their garden, some even squashing their little noses up to the glass. Lots of people have celebrated their birthdays with their friends and family by holding their birthday cakes up to the camera for others to see.

Eating alone together online has also started to become popular again among families and friends. I remember a few years ago, when Skype was becoming mainstream, some of us tried it as an experiment. For example, when I was in South Africa on sabbatical, I had a Skype dinner with a friend back in the U.K. It was nice to catch up with her while doing something, but the eating part actually felt quite odd. We had both served ourselves something simple—a pasta dish—and started eating at about the same time. But somehow picking up our knives and forks together did not synchronize, and the eating of the meal did not feel natural. The smells, tastes, and noises of eating together were lost in translation.

At the end of a tiring day of back-to-back remote work meetings, I now look forward to a FaceTime chat with a friend or two, glass of wine in hand. Of course, it is no substitute for the real thing, but it can be surprisingly relaxing and enjoyable. We make sure we have a good laugh, crack some jokes, and try to see the funny side of life. And then it’s dinner, Netflix, and the 10 o’clock news before going to bed.

Another Groundhog Day in these strange times.

Remote numbers: April 9, 2020

The day before the coronavirus lockdown started in the U.K., I had a smart meter fitted in my house. After the engineer finished, he walked me through all the various functions shown on the digital display. A dashboard of numbers provides all sorts of stats and data about how much electricity and gas you are using and how much they cost per hour, alongside an easy-to-read traffic-light barometer that moves into red bars if you are using a lot of energy (e.g., when boiling a kettle) while rewarding you with green bars when you are being energy efficient. The idea is that you use the various numbers and bars to change your behavior, and in doing so, reduce your energy usage and save money.

I looked at the display a few times but did nothing to change my own behavior. Quite the opposite, in fact. I started using more electricity and gas, making more cups of tea, cooking more meals, spending more hours in front of my laptop and TV, and doing more washing—all a result of being stuck at home 24/7. The best place for the display? Hidden in a drawer.

Meanwhile, like everyone else, I have been gripped by the numbers that come out each day about coronavirus—uncomfortably so. The tally of new cases and new deaths rises daily. At first, two or three people dying was considered shocking. Now we are up to nearly 1,000 a day in the U.K. It is no longer shocking but expected. We have all become engrossed by the graphs that the scientists generate to help the layperson understand what the numbers mean with respect to where we are in the quest to flatten the curve. They project how steep the curve is each day relative to day zero. The color-coded ones show where the U.K. is relative to other countries we might care about. I catch myself comparing how we are doing against the U.S. or Italy—thinking we are better off or not doing as bad. Why are we being shown this, as if it was a competition? To make us feel better? Comparative graphs are a mechanism commonly used in behavioral change, known as social norms. By seeing how well you are doing relative to others (e.g., peers, other families, neighboring cities or countries), you can relax if you are below the others or worry if you are above—there is a loud and clear indication of whether you are using more or spending more (if it is exercise, the reverse is true).

More and more of these visualizations are appearing, including Sky’s “Coronavirus: How many people have died in your area? Covid-19 deaths in England mapped.” Residents of remote areas like Suffolk can let out a big sigh of relief that there are no big blobs nearby. Those who live in London or other densely populated areas, on the other hand, will notice big blobs splatted over their home turf. No wonder so many Londoners flocked to the countryside when they could—that is, before those who live there full time told them where to go.

For the most part, there is little we can do other than worry when looking at these comparative coronavirus graphs. They are fodder, too, for the media and politicians. For example, this headline: “Singapore Wins Praise For Its COVID-19 Strategy. The U.S. Does Not.” A CNN headline was more in tune with the way science happens, through competing predictions and hypotheses: “New U.S. Model Predicts Much Higher Covid-19 Death Toll in UK. But British Scientists Are Skeptical.” The U.S. team predicts that nearly 70,000 will die in the U.K. The British scientists, on the other hand, predicted only 20,000 to 30,000 would die in the U.K., based on their brand of mathematical modeling. Who do we believe?

It goes without saying that mathematical models need lots of data in order to make accurate predictions. When predicting the weather, a tsunami, or an earthquake, millions of data points are used. The current pandemic, however, in comparison has relatively few data points that can be used. It would be hubris not to remember the failure of Google’s Flu Trends program a few years back, when its developers claimed, based on analyzing people’s search terms for flu, that they could produce accurate estimates of flu prevalence two weeks earlier than official data. Sadly, it failed to do this for the peak of the 2013 flu season. Then, they had access to big data—masses of it. The current modelers only have access to small data—very little of it. Let’s hope all the lockdown restrictions that have been put in place in nearly every country, based on current predictions and remote numbers, fares better.

We can but hope.

Remote tracking: April 13, 2020

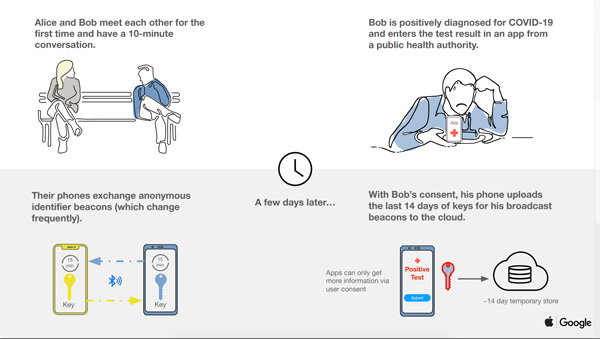

It is great to see tech companies coming together to help curb the coronavirus. Apple and Google have been collaborating on a platform that could help governments worldwide monitor, track, and manage the pandemic more effectively. Their proposed system works by using Bluetooth and encryption keys, enabling data collection from phones that have been in close proximity with each other. From this data, it can be inferred who else phone owners have been close to for a set period of time (e.g., the quarantine period of 14 days). Users can also alert health authorities if they have been diagnosed with Covid-19; conversely, the system can text users if they detect that their phone, and indirectly themselves, have been in close contact with someone who has been diagnosed with the virus. The term coined for this new form of remote tracking is contact tracing, as illustrated by Apple and Google’s graphic (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Apple and Google’s contact tracing system.

If everyone opted in to the system and carried their phone at all times, it could prove an efficient way of letting people know to self-isolate before they unwittingly spread the virus to others. Epidemiologists would also be able to analyze massively more data and be able to develop more accurate predictions. Governments could be better informed about the efficacy of introducing different policies and restrictions about human movement. It seems to be a win-win. However, it requires fairly universal buy-in to the philosophy and the practice as the best way to stop the global spread of the virus. There may be some resistance when it comes to privacy concerns. But such worries need to be weighed against the potential gains of having a pervasive tracking system in place whose sole objective is for the greater public good.

One way to address these concerns is to reassure the public. Much thought has gone into how to avoid unnecessary data collection; Google and Apple’s proposed method of contact tracing is limited in what it tracks and how the data it collects is stored. Compared with GPS that tracks people’s physical location, their proposed use of Bluetooth technology is to pick up signals of only those mobile phones that are nearby, sampled every five minutes. Hence, the data collected won’t know that you were on a bus or in the supermarket at a certain time. It will know only that you were close to a person who has just been diagnosed with Covid-19. This is an important point to be really clear about—as to how much of what someone is doing is actually being tracked. It also helps to address privacy concerns if the data being collected is encrypted.

To enable such a tracking system to have widespread uptake, governments can either be authoritarian and imposing (as is the case in several countries in Asia) or democratic and encouraging—through educating, persuading, incentivizing, and nudging people to opt in. However, this takes time, during which dissenting voices in the press and on social media, together with conspiracy theorists, may create a groundswell of worry. To overcome scaremongering and anxiety requires open debate about what is acceptable and what is not, and how this can change over time and in different cultures and circumstances. Consider CCTV: It is now widely accepted in many countries as a technological deterrent against crime, yet when it first became mainstream in some countries like the U.K. and Germany, many people were up in arms, not least the Snoopers Charter. Since then, however, public opinion has changed. Police authorities found the cameras very useful in helping in their investigations and through acting as a deterrent. Nowadays, cameras of every shape and size have become the order of the day, from webcams worn by frontline workers to massive multiplex CCTV security setups in shopping malls.

Part of my research agenda is to investigate public opinion and sentiment about “creepy data.” We carry out studies to see which technologies people find acceptable and which make them fell uncomfortable, compromised, or threatened. In the early days of mobile phones, I worked on a project called Primma (https://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/primma/) that investigated how to enable people to manage the privacy of their own mobile devices within a framework of acceptable policies. One of our user studies, called Contravision, explored public reactions to a fictitious future technology called DietMon. The proposed tech enabled people who seriously needed to lose weight to track their calorie consumption by providing them with information on their phones about the amount of calories in the food they were contemplating eating. A chip was also embedded in their arm that sent data about their physiological states to their GP. Participants were shown either negative or positive videos of how people managed their everyday lives when using such monitoring tech. Their reactions were mixed. Some people were grossed out; others saw the potential benefits of the system. Importantly, it resulted in an open debate where a diversity of different perspectives was explored—in sharp contrast with the scaremongering that the media often presents to the public. In the end, many different opinions and concerns were voiced.

In another study we conducted (see https://quantifiedtoilets.com/), which investigated concerns over the use of tracking in public, one person said, “Privacy is important. But I would like to know if I was sick and this is a good way to do it.” This sentiment is at the heart of the current contact-tracing dilemma.

Closing words

My next blog is called “Remote nurturing.” I extol the virtues of all the latest crazes that promote being social and feeling human—pub quizzes, making bread, street concerts, growing vegetables. Now that some of the lockdown restrictions are beginning to ease throughout the world, we can begin to establish a new normal, helping each other out while we gradually discover what it means to be together again—albeit at an indefinite social distance.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Johannes Schöning for editing the blog entries for this article.

Posted in: Covid-19 on Thu, May 28, 2020 - 1:46:39

Yvonne Rogers

View All Yvonne Rogers's Posts

Post Comment

No Comments Found