Authors: Ron Gabay

Posted: Thu, May 21, 2020 - 2:58:42

In recent years, design has established itself as a strategic business asset that helps organizations innovate and grow. From first being associated with aesthetics, design has become a measure for user centricity and an engine for creating meaningful experiences and improved business performance. An increasing number of organizations recognize the value of design and seek to interweave design capabilities into their operations. With the ongoing market pressures to stay relevant and competitive through innovation, organizations face the multifaceted challenge of integrating business and design, while also experiencing an unprecedented rate of change.

By examining other periods of disruption and innovation in human history, we learn that this kind of challenge is not completely new. The Scientific Revolution, much like today’s market, was a period of disruption that brought with it an unprecedented rate of change. Different disciplines and groups, similar to business and design professionals today, started collaborating on topics that at that time were considered distinct and isolated. Throughout the years, research about the Scientific Revolution has produced insights about interdisciplinary work and its role in generating breakthroughs. This article examines these insights in order to provide perspectives on how to interweave business and design in the current disruptive era. In addition, to put these perspectives in context, a critical review of design sprints is offered.

The business value of design

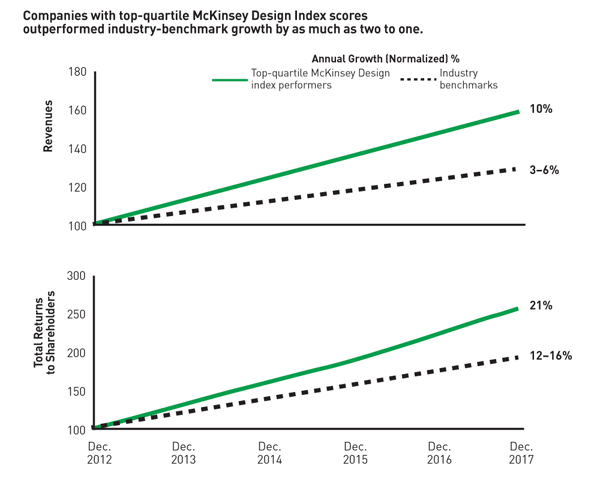

As organizations become data driven and seek to quantify their decision-making processes, collecting data about the business value of design is key. Today, we not only feel that good design is good business, but we also have the data to prove it. This makes design compatible with the modern, data-driven business world. Consultancy firm McKinsey conducted one of the most extensive studies on the financial value of design in 2018, collecting more than 2 million pieces of financial data and recording more than 100,000 design actions [1]. By correlating design actions (e.g., appointing a chief design officer or establishing a user satisfaction matrix) and financial performance (e.g., revenue or shareholder returns), McKinsey found correlations between investments in design and improved financial performance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Source: McKinsey Design Index, The Business Value of Design Report, 2018 [1].

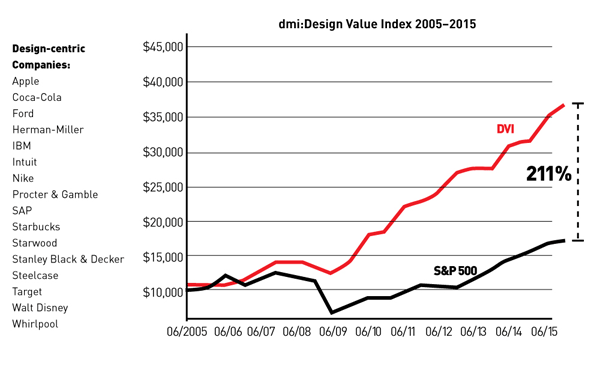

Another study conducted by the Design Management Institute (DMI) tracked the share value of design-centric companies. The DMI monitored investments in design and their impact on companies’ performance relative to the S&P 500 Index. Over a 10-year period, the Design Value Index (DVI) showed that design-centric companies have outperformed the S&P 500 Index by more than 200 percent [2] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Source: DMI Design Value Index, Design Management Institute [2].

The data-driven understanding of the business value of design amplifies the question of how best to integrate business and design. To answer this question, one must first gain a deeper understanding of business and design, in particular their differences.

How business and design are different

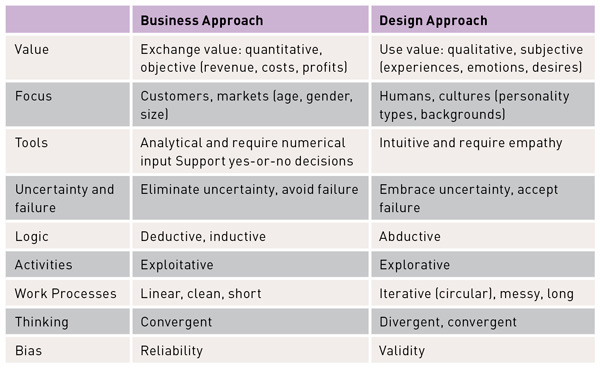

The first dimension in the multifaceted challenge of integrating business and design in today’s world is their unique and distinct nature. Table 1 highlights some of the key differences between business and design. By examining various criteria, it is clear that business and design differ in many aspects.

Table1. Business and design comparison [3].

While the comparison may simplify the complexity and interconnectedness of business and design, its aim is to provide a viewpoint, a viewpoint that emphasizes that business and design are opposing yet complementary in nature. Moreover, the table reveals that business and design are also incommensurable (do not share a common measure). This incommensurability presents itself through different terms, methods, and processes. Thus, any attempt to lead business and design integration must address their unique characteristics and incommensurability. The failure to recognize and properly address the lack of common measures may lead to tension, misunderstanding, and even hostility between business and design professionals. To learn how to deal with incommensurability and prevent it from hindering innovation, it is worthwhile to investigate the Scientific Revolution.

The Scientific Revolution and incommensurability

The Scientific Revolution, which took place during the 16th and 17th centuries, was a disruptive period that generated many breakthroughs. During this period, new knowledge about physics, biology, mathematics, astronomy, and chemistry emerged, transforming how people view the world. In his influential book The Structure of the Scientific Revolutions [4], Thomas Kuhn reviews the history of science. Kuhn, an American philosopher of science, shares his observations about different scientific theories and their relationship to one another. He identifies the presence of incommensurability when he fails to compare and see developments from one scientific theory to another.

The inability to compare or see how one theory relates to the next is rooted in the fact that different scientific groups worked independently and used different terms and methods. The lack of common measures created a situation where groups were neither able to communicate nor exchange valuable information. Moreover, because of this incommensurability, relevant information, and even solutions that could have helped other groups create breakthroughs, were simply overlooked.

Kuhn’s Loss—a significant barrier for design-led innovation

According to Kuhn, incommensurability became a significant barrier for breakthroughs and led to scientific stagnation. The main reason for this stagnation was that different scientific groups were simply not able to communicate. Groups could not understand and benefit from previous knowledge or perspectives due to inconsistency and unfamiliarity with one another’s terms, methods, or contexts. This notion of not being able to funnel and leverage existing knowledge toward a new paradigm is referred to as Kuhn’s Loss.

Business and design professionals, much like different scientific groups during the Scientific Revolution, have their unique terminologies and methods. For example, as the table above shows, business perceives an individual as a customer who is defined by terms such as age, gender, or income. Design, on the other hand, views customers as humans and studies their personality, needs, and desires. Overall, as design-led innovation becomes a new paradigm founded on business and design integration, facing incommensurability is inevitable. Therefore, organizations that wish to maximize the powers of design-led innovation must address the concept of Kuhn’s Loss.

No-Overlap Principle

To avoid or minimize the negative effect of incommensurability, Kuhn developed the No-Overlap Principle. The principle suggests that terms must not have an overlapping meaning or reference, and that when one term is used, it must be explained with its relevant context. For instance, “to learn the term liquid, one must also master the terms solid and gas” [5]. In the world of innovation, a No-Overlap Principle could be valuable for various reasons.

First, today’s world presents complex challenges that require companies to adopt interdisciplinary approaches. For business and design teams to work effectively, they need to be able to communicate and understand each other. For example, exchange value (revenue, costs, and profits) needs to be explained alongside use value (experience, emotions, and desires). Alternatively, customer or market analysis ought to be accompanied by a qualitative evaluation that includes personality types, cultural backgrounds, and traditions. Second, in a world that constantly changes and in which technology is easily accessible, human capital becomes the most significant source of innovation. The No-Overlap Principle supports some of the basic human needs from Maslow’s hierarchy: recognition and respect [6]. In essence, the principle expresses to business and design professionals that they are both essential contributors to innovation and success.

A critical review: Design sprints

With the increasing attention that the business value of design receives, companies seek to interweave design into their operations. One way that design is being introduced to companies is through the design sprint, a five-day framework for solving challenges by applying design tools and methodologies [7]. A design sprint uses design activities such as research, user journey creation, sketching, and prototyping to efficiently generate meaningful concepts. Design sprints are becoming a popular multidisciplinary method for design-driven innovation. Since the goal of a design sprint is to leverage design methods and processes in the business environment, we must ask ourselves whether design sprints satisfy the No-Overlap Principle.

The good. Design sprints introduce design to organizations and non-designers in a bite-size, five-day process. A sprint is usually a controlled environment where design activities and methodologies can be introduced to various stakeholders. The fact that sprints take place in a neutral environment (usually not where daily business meetings take place) creates the opportunity to generate the right physical and psychological setting for learning, experimenting, and engaging with design for the first time. The physical and psychological distance from daily routines can help loosen some of the participants’ deeply ingrained business mindsets and defuse tensions or preexisting hostility.

Design sprints also provide organizations and non-designers a degree of certainty about the design processes, steps, and expected outcomes. The following is an example from the website of Google Ventures (creators of the design sprint):

On Monday, you’ll map out the problem and pick an important place to focus. On Tuesday, you’ll sketch competing solutions on paper. On Wednesday, you’ll make difficult decisions and turn your ideas into a testable hypothesis. On Thursday, you’ll hammer out a high-fidelity prototype. And on Friday, you’ll test it with real live humans [8].

The five-day, step-by-step framework corresponds with how businesses operate and assess processes. Overall, design sprints can be an effective way to introduce design to non-designers because they simplify design in a manner to which non-trained participants can relate. In other words, a design sprint does satisfy, to some extent, the No-Overlap Principle through familiarity with terms and methods.

The bad. Design sprints have a very clear set of rules and milestones that make design relatable and comprehensible to non-designers. However, design sprints also erode some core qualities of professional design, which, in turn, minimize its potential impact. First, design sprints portray design as a linear process. Much like a recipe, a sprint provides the notion that if only the predefined steps are followed, an innovative Michelin-star dish awaits at the end of day five. Design sprints provide participants the false impression that design is a clean, short process when in reality it is often iterative, messy, and long.

Moreover, the design sprint’s gate-like process pushes participants to explore and arrive at meaningful directions within a short, predefined period. This future-oriented exploration is complex and involves many unknown territories where “mistakes” are inevitable. Yet in the search for innovation, mistakes are actually experiments. This notion, coupled with the usual business pressure to deliver, could harm and limit the potential impact and quality of design. Essentially, during the sprint, non-designers are asked to produce quality design work by engaging in activities that are often new and counterintuitive to them. We must question whether participants will truly immerse in exploration and will be able to refrain from the old business habit of associating potential mistakes (experiments) with failure.

Overall, a design sprint may satisfy the No-Overlap Principle by introducing design terms and methodologies to non-designers. Yet it fails to provide the broader context and deep understanding for design. If an organization is not design-centric, it will not be able to develop or scale the outcomes of a design sprint, as exceptional as they might be, in a meaningful manner. Essentially, running design sprints without a border integration of design into business will limit an organization’s ability to innovate because it alters and reduces design to its lowest common denominator.

Conclusion: The future of business and design integration

Design-led innovation has established itself as a catalyst for growth and differentiation. Across the globe, organizations seek to build and scale design capabilities to tackle current problems and to shape the future. To unleash and interweave the powers of business and design as a source for innovation, it is important to recognize the extent to which they differ and that they do not share a common measure. Interdisciplinary frameworks such as design sprints do help in democratizing design by reducing design to a level that non-designers can relate to. Nevertheless, reducing design may actually limit its puzzle-solving powers and long-term integration within the business context. I believe that organizations that wish to become design-centric and reap the fruits of interdisciplinary work must understand that the lack of common measure between business and design does not imply shifting toward finding the lowest common denominator. Instead, organizations should hire and invest in specialized professionals who can continue to perfect their skills while addressing the concept of Kuhn’s Loss.

The key is finding T-shaped individuals—experts in their own domain who are able to collaborate across disciplines or functions. These individuals will help organizations avoid the trap of overspecialization, which leads to the loss of flexibility, openness, and curiosity—all cornerstones of innovation. Ultimately, within the organizational structure, organizations must find the right people and incentivize them to work together because, as C.P. Snow noted in his famous 1959 book The Two Cultures, “The clashing point of two subjects, two disciplines, two cultures—of two galaxies, so far as that goes—ought to produce creative chances. In the history of mental activity, that has been where some of the breakthroughs came” [9].

Endnotes

1. The Business Value of Design - McKinsey Report. 2018.

2. Rae, J. Design value index exemplars outperform the S&P 500 index (again) and a new crop of design leaders emerge. dmi: Review - Design Management and Innovation 27, 4 (2017), 4–11.

3. Gabay, R. Breaking the wall between business and design—Becoming a hedgefox. Design Management Journal 13, 1 (2018), 30–39.

4. Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Second Edition, Enlarged ed.). The Univ. of Chicago Press, 1962.

5. Oberheim, E. and Hoyningen-Huene, P. The incommensurability of scientific theories. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2018 Edition), E.N. Zalta, ed.

6. Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review 50, 4 (1943), 370–396.

7. Knapp, J., Zeratsky, J., and Kowitz, B. Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days. Bantam Press, London, 2016.

8. The Design Sprint - Google Ventures (GV) Official Website.

9. Snow, C.P. The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution. Cambridge Univ. Press, 1959.

Posted in: on Thu, May 21, 2020 - 2:58:42

Ron Gabay

View All Ron Gabay's Posts

Post Comment

@Yoav Pridor (2020 06 02)

Great stuff Ron. Very interesting.

@andrew723 (2025 04 27)

The Scientific Revolution, spanning roughly from the 16th to the 18th century, reshaped humanity’s understanding of the natural world. Giants like Galileo, Newton, and Kepler didn’t just challenge the orthodoxy—they redefined how knowledge could be constructed. While typically framed through the lens of science, this period also holds powerful lessons for design-led innovation today. Direct View LED Panels

@evelyn lucas (2025 08 28)

It highlights how breakthroughs in science can inspire new ways of thinking in design and innovation. Just as the Scientific Revolution transformed society by challenging established beliefs, embracing experimentation, and fostering collaboration across disciplines, design-led innovation encourages organizations to question assumptions, explore creative solutions, and integrate diverse perspectives. By drawing on these historical lessons, outsource bpo services businesses and innovators can develop products, services, and systems that are not only functional but also transformative, driving long-term growth and cultural impact.