Authors: Phoenix Perry

Posted: Fri, January 18, 2013 - 2:53:17

At NYU ITP in fall of 2012, I created and taught a class focused on embodied play. We explored this question: “How can interactive design create powerful experiences by tapping into our emotions?"

First off, it is worthwhile to put ITP into context. The NYU ITP site states, “ITP is a two-year graduate program located in the Tisch School of the Arts whose mission is to explore the imaginative use of communications technologies—how they might augment, improve, and bring delight and art into people's lives.” It’s a dynamic environment that allows for open experimentation in pedagogy letting me create this one of a kind course based on my personal research at the NYU Poly Game Innovation Lab.

To get students started, we defined embodiment for the sake of the class as a digital experience engaging the whole body. Technologies encouraged for use within projects were Kinect, iOS, Unity, Lilypad, and Ardino. Next, we identified a few key traits of successful interactions. Researching embodied games revealed two main types of user interaction: anachronistic body-mapped control schemes and embodied control systems.

Anachronistic body mapping takes traditional input mythologies and reapplies them to the body, along the way short circuiting potentially new forms of interaction. When it comes to the human body, this kind of control is particularly insidious because it often comes at the expense of the user comfort and possible safety.

For example, in June of 2011, Tetsuya Mizuguchi released Child of Eden with this kind of control scheme. This game is beautifully rendered and is stunning for many other reasons; however, the control system could be improved. Players must stand with their arms held parallel to the floor for nearly the entire duration of the game. There is positively no way a user could play Child of Eden without significant physical discomfort using the Kinect alone. This kind of user experience seems like a stepping-stone toward a more robust design.

Instructions on playing Child of Eden showing an arrow control pad

mapped to hand tracking.

In sharp contrast, embodied control unites player and interface through a holistic map of the player’s complete body into the game space while also considering the affordances of lived experience. These are the types of designs leading towards the most organic kind of engagement. An exceptional embodied control system exists in Deepak Chopra’s Leela. It accounts for a user’s whole form in the game space while challenging past affordances accumulated within the human body during play. With a focus on opening and expanding the body, the interaction design is similar to the style of movement experienced during a yoga class.

Screen capture from Deepak Chopra’s Leela showing the breath

control level.

With this understanding, students began crafting experiences of their own. Design was approached as an evolving process. We went through the following steps: conceptual development, paper interfaces, testing, iteration of the interaction models, an optional round of testing, creating digital prototypes, and a final round of testing to gauge the success of the evolution of the project. Since emotional states are not always easily observed, 3rd-wave testing strategies proved critical tools for scoring user engagement in these kinds of experiences. Students were encouraged to use open-ended questions, talking aloud, video capture, abstract shapes, and self-reporting during their evaluation processes.

Presented here are a few the most successful projects:

Amelia Hancock: Birdw@tcher

Birdw@tcher plays with tensions that occur between city and wilderness settings. This new media interface whimsically transforms an iPhone into binoculars. Opening a “window” onto a mountainous 3-D space, users traverse the virtual and real worlds simultaneously. Through exploring, it is possible to spot hidden songbirds. As players become immersed in the experience, it begins to evoke a sense of meditation and reverie.

User testing: While testing, Amelia found that many users desired a balance between urban and natural environments. Players suggested enjoying a sense of discovery and found bird watching a surprisingly interesting and fun activity in this context. Multiple rounds of testing helped her to resolve issues of bird placement and user expectations.

Future plans: Currently, the environment that the user explores is limited and fixed. Next, she would like to translate this concept into a GPS-based augmented reality app for children, where they are able to both create their own bird drawings, as well as search for others, in real time and space.

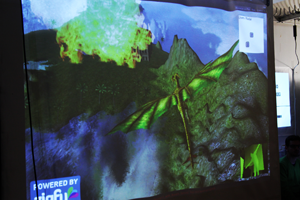

James Borda: The Dragon

The Dragon is a lighthearted experience that incorporates both the body and breath of a player into a game. Transforming into a living, breathing dragon, the user is tracked via the Microsoft Kinect while wearing a headset microphone as they soar around a fantasy world. The installation immediately evoked a sense of joy and childlike abandon in most players. Adults showed a hesitancy to play this game, while children between 8 and 12 immediately jumped into the experience. However, during the ITP end-of-year show, adults brave enough to play visibly enjoyed themselves.

User testing: There is a broad range of natural ability to map one's gestures to the actions of the avatar onscreen. Some people were able to control the dragon very smoothly and intuitively, and others found it very difficult. The most successful group was children ages 8 to 12.

Future goals: James plans to expand the experience into an actual game with multiple levels and goals.

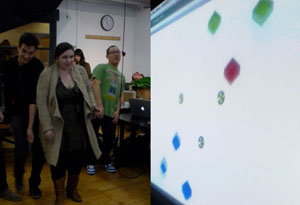

Phan Visutyothapibal: Sound Cubes

Sound Cubes is a multiplayer musical instrument allowing players to work together to create a musical composition. The game begins with six cubes moving up and down on the screen. Each cube contains a sound that complements the other cubes harmonically. Players are represented by circles on screen and are motion tracked via a Microsoft Kinect. When they move into the spaces of a cube, it triggers a sound. By working together, players create cords and melodies. Sound Cubes plays with affect in a more subtle way than the other pieces previously mentioned in this post. This instrument creates a very emergent social dynamic that gives players a sense of mutual collaboration and group involvement. Often users had to squat or jump to catch the animated cubes, which heightened the physical and emotional engagement experienced during play.

User testing insights: Phan explored a range of different interfaces before he finally settled on the animated cubes. His first impulse was to lay the notes out similarly to how they are seen on a piano keyboard. This approach proved difficult to play and led to the second design iteration.

Future goals: Phan ultimately wants this to be an educational tool for teaching music to children.

Without a doubt, many of the other interfaces created in the class were also compelling but these three projects exemplified the tight coupling between the user interaction and the physical body that tends to create the most enjoyable embodied experiences. Teaching a class around embodiment benefited from exploring an iterative design process that allows students a space to rapidly prototype ideas before producing them. Also, 3rd-wave HCI techniques gave students a toolset to quantify their experiences in new ways that particularly resonated with the designers and artists found at ITP. Hopefully, the lessons learned with this class will benefit and enrich the students’ design practices henceforth.

Posted in: on Fri, January 18, 2013 - 2:53:17

Phoenix Perry

View All Phoenix Perry's Posts

Post Comment

@Jerrylo (2024 11 05)

Hi if you’re looking for a fun way to unwind or add some excitement to your daily routine, I highly recommend trying out Winspirit IT’s slot games on your smartphone. You might just find that it’s the perfect way to relax and enjoy some downtime!

@Lily Bryant (2024 11 29)

Embodied games from NYU ITP offer a creative way to engage with learning, blending physical interaction with digital play. They remind me of how math playground uses interactive tools to make learning math fun and engaging for all ages.

@yxchen (2024 12 15)

Fascinating article about embodied gaming! As someone who enjoys both physical and digital card games on Pokemon TCG Pocket, I find the intersection of physical movement and digital interaction particularly interesting. The discussion about creating “organic engagement” really resonates with my gaming experience. Would love to see more research on how traditional card games could evolve with embodied interaction!

@yxchen1994 (2024 12 15)

Really insightful article about embodied gaming! As someone working with numerology and digital interactions at Destiny Matrix, I find the discussion about holistic user engagement fascinating. The way Deepak Chopra’s Leela integrates whole-body awareness reminds me of how we approach personal energy patterns in numerology - it’s all about creating meaningful connections between digital experiences and human consciousness. Would love to see more exploration of how spiritual elements could be incorporated into embodied game design!

@Destiny (2024 12 16)

Really insightful article about embodied gaming! As someone who enjoys exploring digital interactions, I find the discussion about holistic user engagement fascinating. The way Deepak Chopra’s Leela integrates whole-body awareness reminds me of my experience with Destiny Matrix, where I discovered how numbers and patterns can create meaningful personal connections. The emphasis on user testing and emotional engagement really resonates with me. Would love to see more exploration of how spiritual elements could be incorporated into embodied game design!

@yxchen (2024 12 21)

Thank you for this informative article! Speaking of useful financial tools, I’ve been using this BRI calculator for my mortgage planning and it’s been incredibly helpful.

@yxchen (2024 12 21)

Great post! During my breaks at work, I’ve found that puzzle games really help clear my mind. Recently discovered Unblocked Escape Roads and it’s become my go-to for quick brain teasers.

@Eddison Mcgee (2024 12 25)

Eye-catching graphics, simple gameplay but requiring absolute concentration geometry dash lite – this is the challenge you are looking for.

@Yureoi (2025 01 14)

The fact that it demands lightning-fast reactions and run 3 is one of its biggest draws.

@terminuscalculator (2025 01 31)

Terminus Calculator for solving Terminus codes in Black Ops 6.

terminuscalculator

@Harry (2025 02 12)

I just tried Slope Game, and it’s so addictive! The ball keeps getting faster, and it’s hard to control. Give it a try—you’ll want to beat your high score!

@yxchen1994 (2025 02 15)

Really insightful article about embodied gaming! experience the magic of Kingdom Come: Deliverance II and explore the medieval world of Bohemia.

@vivian alva (2025 02 20)

Anyone anyone struggled with level 10? I was pleasantly surprised by its ease and completed it easily on my first try.

thief puzzle

@tom hansky (2025 03 03)

Game discovered by bob the robber

@johnsmith (2025 03 06)

Thank you for sharing this fascinating article about embodied games at NYU ITP! The ideas around integrating emotions and technology in interactive design are truly innovative. I believe these concepts could be expanded and applied to online games as block blast

@Calculadora Gestacional (2025 03 23)

Quer saber em qual semana de gravidez você está? Use nossa Calculadora Gestacional para descobrir! Basta inserir a data da sua última menstruação e a calculadora fará o resto. É rápido, fácil e preciso. Acompanhe cada etapa da sua gravidez com nossa ferramenta online confiável. Clique no link agora para experimentar a Calculadora Gestacional!

@ИМТ калькулятор (2025 03 23)

Вы хотите быстро рассчитать свой индекс массы тела (ИМТ)? Попробуйте наш удобный онлайн ИМТ калькулятор. Просто введите свой рост и вес, и калькулятор мгновенно определит ваш ИМТ. Это полезный инструмент для контроля веса и здоровья. Зайдите на https://imtcalc.online/ прямо сейчас и узнайте свой ИМТ за считанные секунды!

@nailGenie (2025 03 24)

Thank you for sharing this fascinating article about embodied games at NYU

@nailGenie (2025 03 24)

Thank you for sharing this fascinating article about embodied games at NYU. If you’re struggling to communicate what you want to your nail tech, check out NailGenie: Best Nail Design tool

@yxc123 (2025 03 31)

Turn everyday moments into Miyazaki-inspired masterpieces! Ghiblify translates your photos into whimsical animation style.