Authors: Marketa Dolejsova, Hilary Davis, Ferran Altarriba Bertran, Danielle Wilde

Posted: Fri, April 03, 2020 - 3:59:48

Human-food interaction (HFI) is a burgeoning research area that traverses multiple HCI disciplines and draws on diverse methods and approaches to bring focus to the interplay between humans, food, and technology. Recent years have seen an increase in technology products and services designed for human-food practices. Examples include June, an oven with integrated HD cameras and a WiFi connection to enable remote-controlled cooking; PlantJammer, an AI-based recipe recommender that suggests “surprising” vegan dishes from leftovers; HAPIfork, which vibrates and blinks when you eat too quickly; and DNAfit, a service that uses consumer genome data to suggest a personalized diet. Such technologies turn everyday food practices into data-driven events that can be tracked, quantified, and managed online. Often wrapped in techno-optimism, they propose what seem like straightforward solutions for diverse food problems: from everyday challenges with cooking, shopping, and dieting to systemic issues of malnutrition and unsustainable food production. While on the one hand offering visions of more efficient food futures, this techno-deterministic approach to human-food practices presents risks to individual consumers as well as food systems at large. Such risks include the uncertain safety of food products “created” by algorithms, the limited security of personal, often sensitive, health-related data shared via food-tech services, and the possible negative impacts of automation on social food practices and traditions. Smart recipe recommenders, for example, can suggest ingredient combinations that are surprising but unsafe to eat. Personal genomic data shared via DNA-diet personalization services might get misused by third parties such as healthcare insurance companies. Smart utensils might improve one’s diet but they can also disturb shared mealtimes.

Every innovation brings the potential for new problems. Yet these concerns receive only peripheral attention in HFI literature. To date, HFI projects that propose to fix, speed up, ease, or otherwise make interactions with food more efficient far outweigh those reflecting upon the broader, and often challenging, social circumstances of food-tech innovation [1]. We believe the field of HFI would benefit from more critical engagement with the social, cultural, environmental, and political implications of augmenting food practices with technology. Motivated by concerns about the opportunities and challenges in food-technology innovation, we formed an HFI community network, Feeding Food Futures, to focus on this issue. Within the network, we undertake research, develop theory, and organize events and conference workshops to consider desirable future directions of the field. In this article, we focus on three selected workshops to discuss the opportunities and challenges that technology brings to the table, and propose possible responses in HFI design and research.

HFI Workshops: A Conduit for Critical Debate

We report our observations from three HFI workshops, undertaken at CHI, Montreal; DIS, Hong Kong; and DIS, San Diego [2,3,4,5]. These workshops brought together diverse participants to reflect on HFI issues through hands-on, performative activities and group discussion. At all workshops, food was both primary theme and edible material, enabling practice-based, sensory-rich reflection. Activities involved collaborative crafting and tasting as well as foraging and speculating, supported by various food design props and kits including: Food Tarot cards to provoke future food imaginaries and the HFI Lit Review App to search and categorize the corpus of existing HFI research publications. We also brought, bought, and found various food-related boundary objects and made artifacts in-situ, including a DIY paper constructed from foraged food waste and personalized menus customized to DNA test results. Each workshop gathered participants of diverse backgrounds and used a variety of HFI methods and techniques: ethnographic research in food communities, experimental food design, food-oriented performance art, DIY food biohacking, as well as the prototyping of practical food-tech products. These diverse, at times contrasting, approaches to HFI supported polarized, friendly debates about the desired role of digital technology in food cultures and the contributions we might expect from HFI research. We highlight six debates that stood out in our workshops, and whose importance was recognized by participants. These debates highlight important issues within HFI and can help us to springboard desirable future developments of the field.

Debate #1: Human agency vs. technological efficiency

At CHI 2018, participants introduced an AI-based recipe recommender that suggests ingredient combinations using deep learning and a recipe/image embedding technique [6]. The recommender aims to enhance human gastronomic creativity by suggesting surprising and spectacular recipes. It can suggest extravagant flavor combinations—supposedly beyond the limit of human imagination—as a provocative starting point for food experimentation. For some participants, such data-driven automation presents an opportunity for exciting culinary practices. Others suggested a fine line between enhancing and reducing, even removing, users’ creative engagement with food preparation. They suggested that using the recommender puts people on autopilot, as the algorithm becomes the chef. While gains are made in efficiency, the playful, creative, educational, and sensory elements of cooking may be lost. The debate foregrounded the need to maintain a careful balance between human agency and technological efficiency in AI-based food experiences.

At DIS 2018, participants cooked pancakes in two ways: 1) using PancakeBot, a machine that prints pancakes based on drawings made in custom software; and 2) using a stove and a frypan (Figure 1). With PancakeBot, the cooks’ engagement was mediated and constrained largely to preparation: They imagined, then drew a shape on rudimentary software, positioned a plunger containing the batter, and hit a virtual button to begin the “fully automated” pancake-making process; then they monitored the performance of the robotic chef. In contrast, using the frypan required embodied, in-the-moment, improvisational engagement with food materials and cooking equipment. The cooks often overlooked the fact that their activities were mediated through tools; rather, they seemed guided by their senses. Reflecting on these differences, we determined that future digital cooking technologies should include mechanisms to enable human intervention in emergent, improvisational, and embodied ways that go beyond simply instructing a machine to prepare food.

Figure 1. PancakeBot.

Debate #2: Digital technology vs. the materiality of food

With PancakeBot, the machine’s affordances shifted the way we engaged with the organoleptic qualities of the pancakes—the taste, color, odor, texture and other qualities inherent to the materiality of food and its ability to stimulate our senses. The machine’s functionality oriented our attention toward the visual aesthetics of our anticipated pancakes, to the detriment of all else. Excited by what the technology seemed to promise, we adapted the pancake-batter recipe to achieve better flow through the machine’s extrusion mechanisms, disregarding the impact of this adjustment on taste. Further, the spectacular PancakeBot influenced our activities when cooking pancakes using the frypan: After using PancakeBot, we began to prioritize the shape of our pancakes in the pan, irrespective of the impact on taste. This shift to privilege visual aesthetics over other organoleptic qualities demonstrates a key risk of inserting digital technology into material practice. Depending on how technologies are designed, they can cause users to disregard important sensual qualities that sit at the core of material cultures. On recognizing this tendency, we determined that digital enhancements should add to, rather than substitute for, the material richness of food experiences and privilege the complex, sensual nature of food and eating over technological capabilities.

Debate #3: New and clean vs. old and messy

At CHI 2018, one participant presented “DIY Kit for Supermarket ‘Chateaus’ of Hybrid Wines” [7], a wine-fermentation kit that enables users to make wine from table grapes as an alternative to standardized off-the-shelf wines (Figure 2). The kit provoked discussion about the contrast between “new” food technologies aiming for “clean” food practices and “old” traditional food techniques, such as wild fermentation, that support “messy” practices and experimental human-food entanglements. While we agreed that food-tech designers need to ensure the safety of their designs, we also recognized the need to support and revive messy, experimental, and playful approaches to food and wine making. We felt new food technologies should nurture consumers’ curiosity for experimentation and prompt rediscovery of traditional and diverse food knowledge, rather than merely supporting efficiency and safety through standardization.

Figure 2. DIY wine kit.

At DIS 2018, a rich discussion ensued about how one’s grandmother’s pasta recipe is much more than a combination of ingredients—it has cultural, social, and emotional meaning. As demonstrated by Mother’s Hand Taste (Son-Mat) by Jiwon Woo—an artwork that examines how the bacteria on a person’s hands impacts the flavor of their cooking—human-food practices can also be a collaboration with bacteria. Such collaboration is expressed in commonly recognized ways (e.g., making cheese, yogurt, wine, kimchi, and other fermented foods) and in perhaps more subtle ways (e.g., recognizing the cook’s microbiota as an impactful ingredient—what Koreans call the “hand taste” of the food). At DIS 2018, we used Steven Reiss’s “16 desires” [8] as a roadmap to investigate the values that shape our food choices and experiences. We recognized that desires are complex and nuanced, whereas engagement with desires through food-tech is often simplistic. This realization exposed a critical limitation of food technologies: It is not only the material messiness of food that should be taken into consideration when designing food technologies, but also the conceptual messiness and complex idiosyncratic nature of desire that must be considered.

Debate #4: Techno-determinism vs. contextual sensitivities

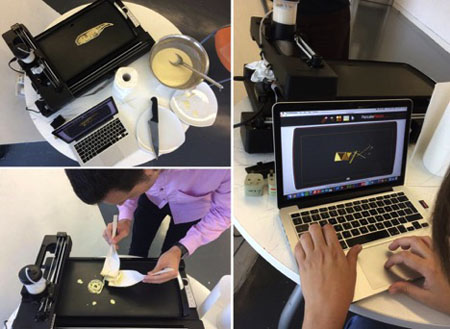

Food standardization and simplification was further unpacked at DIS 2019, through a DNA-based menu—a dinner for two—introduced as a boundary object. Gene-based personalized nutrition (PN) is a growing trend that involves diet customization using personal genotypic data. The dinner for two was based on DNA test results obtained via a commercial genetic testing service. The meals contained the same ingredients in different proportions—adjusted according to DNA predispositions. Diner 1’s DNA test suggested an increased risk for type-2 diabetes. Therefore, she had a smaller portion of potatoes and plain blueberries instead of blueberry cake for dessert, although she said she would much prefer eating the cake. Her test also indicated a higher susceptibility to alcohol addiction. Her wine glass was thus served half-full. In contrast, Diner 2 had an open wine tap, as her DNA showed low risk of alcoholism. This provocative menu initiated a debate about the determinism of PN, wherein supposedly precise biodata is given precedence over taste preferences, or social and cultural background. Participants highlighted potential negative impacts on social food traditions, asking: Will we still eat together when our food practices are personalized and mutually incompatible? Further, personal and sensitive data exposed by the menu raised questions about privacy and misuse of data by third parties, such as health insurers or pharmaceutical companies. This example highlights the need for HFI to carefully consider the impact of technological interventions on the varied contextual sensitivities embedded in food practices.

Debate #5: Human-food interactions are socioculturally situated

At CHI 2018, we mapped food-tech trends onto the Montreal foodscape using our Food Tarot tool: a card deck presenting 22 imagined diet tribes to illustrate emerging food-tech practices (Figure 3). For instance, the tribe of Petri Dishers only eat in-vitro grown meat; Datavores are Quantified Self aficionados who eat according to self-tracking data.

Figure 3. Food Tarot cards.

Inspired by the Food Tarot, local participants mapped the cards with local venues—for example, Gut Gardeners with a local fermentation workshop and Food NeoPunks with the Loop Juice shop that makes juice from leftover fruits [9]. They went to the selected venues, foraged for paper-based food waste, and crafted a locavore version of Food Tarot cards; then asked the other participants to forage paper waste at CHI and craft a collective CHI food-waste card. While crafting with the foraged trash (Figure 4), we discussed the situated nature of human-food practices, highlighting that such practices cannot be interpreted from a research lab or a design studio but rather should be explored through fieldwork “in the wild.”

Figure 4. Making a Food Tarot card from CHI paper waste.

Debate #6: Innovation and inequity

At DIS 2019, we conducted a “walkshop” to forage for local food items and dining experiences. The conference location, in the resort area of San Diego SeaWorld, provided a controversial context for this exercise: Local dining options involved expensive hotel restaurants or fast-food chains and pizza parlors. While eating pizza and sipping soda from gigantic plastic cups, we talked about unequal socioeconomic access to “good” (healthy, sustainable) food products and food technologies designed to support “good” food practices (Figure 5). We acknowledged our privilege, having “the luxury of choice” in this extreme food landscape. Many food-tech products are available only to people from privileged socioeconomic backgrounds. Non-access due to income, education, or digital illiteracy can marginalize individuals and social groups. Food-tech innovation thus risks extending existing, and creating new, socioeconomic inequalities.

Figure 5. HFI walkshop in San Diego.

Thoughts on the Future of HFI Design and Research

During the DIS 2019 walkshop, participants documented their experiences through written notes, sketches, photos, and found or bought food items and we collaboratively crafted an HFI Zine (Figure 6). The zine has been extended by the workshop organizers to serve as a condensed summary of discussions and debates drawn from all three workshops. Not a manifesto or a fixed set of guidelines but rather a humble set of ideas, the zine offers suggestions on what HFI design and research could do in the future. For example:

To leverage and support food as a creative, material, equitable, and situated sociocultural practice, HFI should:

- Open spaces for experimentation and learning, rather than deliver quick-fix solutions catering to consumers’ convenience

- Support broad socio-economic access and help reduce inequalities on the global food market rather than expanding them

- Take place ‘in the wild’ to reflect contextual sensitivities of local food cultures and practices

- Reflect the socio-culturally diverse, complex, sensory-rich nature of human-food practices, rather than prioritising standardisation by default

- Be culturally diverse

- Complement existing food traditions, rather than replace them

- Keep consumers’ active and creative engagements central to food-tech practices

- Be mindful of consumer privacy

- Be concerned with local human-food-tech interactions, as well as systemic, larger-scale implications of food-tech innovation.

Figure 6. HFI Zine.

Feeding Food Futures: Community and Critical Discussion

The workshops discussed here illustrate how new food technologies can have ambivalent impacts on food cultures. Food-tech products and services designed to improve practices and solve problems often create new problems of their own. This is not to say that we should strive for technology-free food futures. Food-tech innovation can make important and necessary contributions to food culture; technology can be incorporated meaningfully into existing social practices. With environmental uncertainty and public health crises, food practices need to change and technological innovation can facilitate the needed changes. However, we must be mindful of the challenges, and carefully consider the sociocultural impacts that food-tech innovation may have on food-related practices.

The debates we highlight here reflect important issues that we believe HFI researchers should consider as food-tech innovation moves forward. We recognize continuity in the conversations we initiated within the workshops, and acknowledge the importance of increasing the diversity of stakeholders at the table. To that end, we will continue to promote events where such discussions can take place. Our long-term aim is to nurture a multidisciplinary HFI community that considers perspectives of food-oriented researchers, designers, practitioners, and (human and nonhuman) eaters of diverse backgrounds. With these goals in mind, we initiated the Feeding Food Futures (FFF) network to support critical, experimental, in-the-wild HFI research and discussion. Our intention is for FFF to encompass a broad spectrum of HFI-focused initiatives, such as community workshops, an HFI summer school, and further co-authored publications. Critically, we do not see ourselves as having a monopoly on FFF. The success of FFF hinges on involving diverse scholars and practitioners. We will only feed the future of food in sustainable ways if we encompass a broad set of perspectives. We thus extend an invitation to interested others to join us on this journey. We look forward to future collaborations to critically reflect on the future of human-food-technology ecosystems and to collectively shape a vibrant, rich, and diverse foundation for HFI.

Acknowledgments

We thank our workshop co-authors and participants, past, present and future, who are key to shaping FFF and HFI activities and discussions.

Endnotes

1. Altarriba Bertran, F.*, Wilde, D.*, Segura, E.M., Pañella, O.G., León, L.B., Duval, J., and Isbister, K. Chasing play potentials in food culture to inspire technology design. Proc. of the 2019 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play. (*joint first authorship)

2.Altarriba Bertran, F.*, Jhaveri, S., Lutz, R., Isbister, K., & Wilde, D.* Making sense of human-food interaction. Proc. of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. (*joint first authorship)

3. Dolejšová, M., Khot, R.A., Davis, H., Ferdous, H.S., and Quitmeyer, A. Designing recipes for digital food futures. Extended Abstracts of the 2018 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

4. Dolejšová, M., Altarriba Bertran, F., Wilde, D., and Davis, H. Crafting and tasting issues in everyday human-food interactions. 2019 ACM Conference Companion Publication on Designing Interactive Systems.

5. Vannucci, E., Altarriba Bertran, F., Marshall, J., and Wilde, D. Handmaking food ideals: Crafting the design of future food-related technologies. 2018 ACM Conference Companion Publication on Designing Interactive Systems.

6. Biswas, A., Mawhorter, P., Ofli, F., Marin, J., Weber, I., and Torralba, A. Human-recipe interaction via learned semantic embeddings. Presented at the 2018 CHI Conference Workshop on Designing Recipes for Digital Food Futures.

7. Špačková, I. DIY kit for supermarket “chateaus” of hybrid wines. Presented at the 2018 CHI Conference Workshop on Designing Recipes for Digital Food Futures.

8. Reiss, S. Multifaceted nature of intrinsic motivation: The theory of 16 basic desires. Review of General Psychology 8, 3 (2004),179–193.

9. Doonan, N., Tudge, P., and Szanto, D. Digital food cards: YUL forage. Presented at the 2018 CHI Conference Workshop on Designing Recipes for Digital Food Futures.

Posted in: on Fri, April 03, 2020 - 3:59:48

Marketa Dolejsova

View All Marketa Dolejsova's Posts

Hilary Davis

View All Hilary Davis's Posts

Ferran Altarriba Bertran

View All Ferran Altarriba Bertran's Posts

Danielle Wilde

View All Danielle Wilde's Posts

Post Comment

@XanderFord (2024 07 05)

Personal genomic data shared via DNA-diet personalization services might get misused by third parties such as healthcare insurance companies.

Arlington Drywall Contractor Pros

@steve7876 (2025 03 19)

Personalized diet. These innovations highlight the evolving relationship between food, technology, and human behavior. As HFI research expands, it addresses critical topics such as sustainability, nutrition, and cultural food practices. Researchers explore how digital tools can enhance cooking experiences, promote healthier eating habits, and even encourage mindful consumption. The future of HFI will likely bring even more interactive and intelligent food technologies, shaping how we engage with food on a daily basis.

motorcycle appraisal near me

@Smithjoara (2025 04 18)

This blog, authored by Marketa Dolejsova and colleagues, explores the evolving field of Human-Food Interaction (HFI)—a cross-disciplinary area at the intersection of human-computer interaction, food practices, and technology. The authors challenge the common techno-optimistic narratives by highlighting the complexities, risks, and sociocultural dimensions of integrating technology into food-related practices.

pacote de viagem lençois maranhenses

@Emma32 (2025 05 28)

Feeding the futures of human-food interaction is mind-blowing—tech’s redefining how we grow, eat, and think about food. Even a Kansas City Dui Attorney could appreciate the innovation here, imagining safer, smarter dining experiences ahead. It’s a delicious blend of progress and possibility worth watching closely.

@kim (2025 06 25)

A fascinating look into how technology is transforming our relationship with food.

From smart utensils to DNA-based diets, innovation brings both solutions and concerns.

Cultural traditions and sensory experiences must not be overlooked.

This article explores key debates shaping the future of food-tech.

Discover more on this website.

@justinscott (2025 08 20)

Exploring the evolving relationship between humans and food has been eye-opening for me. I’ve skilled nursing facility Los Angeles realized it’s not just about nourishment but also sustainability, culture, and innovation. I value how modern approaches connect tradition with technology, shaping healthier choices and mindful consumption while redefining how we grow, share, and experience food daily.