Authors: Kyle Boyd, Raymond Bond, Maurice Mulvenna, Karen Kirby, Susan Lagdon, Becca Hume

Posted: Thu, June 08, 2023 - 3:49:00

Do you feel safe when you travel alone? That was a question I asked my girlfriend (now wife) as we took a trip on a relatively empty train when I was visiting her at university. “I always carry my phone with me, but sometimes it's actually worse when the train is full; people watch what you are doing on your phone, and it's very off-putting,” was her reply.

Fast-forward 10 years and we are still very much in the same predicament. People, especially women, can feel vulnerable in certain situations. A 2019 survey [1] by SAP Concur, a company that provides travel and expense-management services to businesses, agrees. The survey revealed that safety is the number one concern for female business travelers. Indeed, 42 percent of respondents said that they have had a negative experience related to their gender. This isn’t limited to gender, though. Our intention is to highlight that people can feel vulnerable because of certain characteristics, including disability or race, and in certain situations.

With the rise of ubiquitous computing, we have the ability to use a plethora of devices that can connect to the Internet. This allows us to work, shop, and entertain ourselves from almost anywhere. Devices and their interfaces have become an extension of our own selves.

In recent decades, smartphones, emails, and instant messaging have been the predominant methods for human-to-human communication. And now with “generation mute” [2], instant text messaging, as opposed to making phone calls, has become the primary use of smartphones. With growing concerns over cybersecurity and privacy, instant messaging apps such as WhatsApp incorporate end-to-end encryption.

Modern text messaging apps allow users to send messages that are discreet in the sense that they are secure. But of course the interaction is not entirely private, since any onlooker could potentially see the user typing and sending a text message. A more discreet interaction might be the use of secret codes to input into the messaging app, which would be indecipherable to onlookers. However, this would add to the cognitive load and require a new communication code. Other apps such as Snapchat have functionality to send messages and photos that are only temporarily available; they are automatically deleted shortly after being viewed. These apps could be considered a “discreet user interface,” since though a spouse or family member might see the message or photo being sent or received, they cannot confirm it by interrogating the user’s stored media. With these examples, digital communication today is discreet in terms of privacy and data encryption during transit; however, the user interaction is not hidden from onlookers. With this can come unwanted attention, as onlookers can view and digest some of the information on your digital device, whether this be texting a friend from the train or doing work on your laptop on an airplane. In 2019, HP conducted a “creepers and peepers” survey [3], asking 3,000 people in the general population and 1,500 staff whether they would look at another person’s computer screen during a flight. Astonishingly, 4 out of 5 look at other people’s screens; 8 out of 10 restrict what they look at on their device just in case people are looking at their screen. This gives rise to questions about device-use etiquette and safety when using digital devices in public, stretching further for interfaces used for finance or security.

As interaction design researchers, we want to consider how design could help. Could we design a hidden user interface for safety purposes? This work is aimed to be both conceptual and thought-provoking.

Discreet User Interfaces

Do you remember the first time you saw the interface on a first-generation iPhone? It was staggering. Swiping, zooming, pinching, and animations that allowed for delight and control. All these new controls that allowed the content to take center stage and be the interface. Edward Tufte was correct when he said that “[o]verload, clutter, and confusion are not attributes of information, they are failures of design.” As interface designers, we strive for simple design that won’t get in the way, that will allow us to complete tasks in an efficient and satisfactory manner, producing interfaces that work. For many use cases, this is the appropriate design methodology to use when it comes to designing interfaces.

But what design methodology should we use if we wanted to create a “discreet user interface”? A discreet user interface is a user interface that looks like it’s doing one thing but actually is doing something entirely different. Alarm bells might start ringing when we put it this way, but that doesn’t mean people are doing anything sinister. Quite the opposite. A discreet user interface could be there to help and protect, even though it is “ethically deceiving” onlookers by preventing them from interpreting what the user is actually doing on their screen.

What was historically known as the “boss key” could be described as a kind of discreet user interface. A boss key is a key on the keyboard (e.g., F10 or ESC) that a user presses in haste during “play time” when their boss is nearby, displaying a fake spreadsheet, business graph, or slides to discreetly deceive the onlooking boss. Other interactions that we could also consider to be discreet interactions, or at least discreet features, include “Easter eggs,” which were hidden features inside Microsoft products. These could also be hidden games, such as pinball or a flight simulator. And of course even smartphones have hidden features, such as shaking the phone to undo an action, facilitated by sensors such as an accelerometer.

With this in mind, and perhaps more intuitively, discreet user interfaces could be those that a user can interact with while preventing an onlooker from knowing that they are using a computer. These interfaces could fall under the definition of natural user interfaces, where the user can interact with digital systems using their eyes, hand gestures, brain signals, and muscle movements, including facial movements. This can include “silent speech interfaces.” For example, Kapur et al. [4] developed the AlterEgo system, which allows people to interact with a computer through neuromuscular activity. Using electrooculogram (EOG) sensing, Lee et al. [5] developed a system that allows users to discreetly interact with computers by rubbing their “itchy” nose. And Cascón et al. [6] developed the perhaps even more discreet ChewIT, a system that allows users to interact with computers via intraoral interactions by essentially sending discreet signals by chewing. While these are very interesting innovations, they require additional hardware and sensors and are mostly at the research and innovation phases.

Another form of discreet user interfaces could be described as “camouflaged user interfaces” or “ulterior user interfaces.” These are interfaces that give onlookers a fake impression of an app’s utility, with its true, ulterior hidden utility known only to the user. For example, while an onlooker might see the user engaging with a mundane weather app, a sports app, a news app, or a shopping list, the user could be performing hidden tasks or sending secret signals in plain sight by interacting with buttons and features that have hidden functions. The interaction might look mundane, but the user could be sending a secret communication. Hence, this ulterior user interface could also be considered a discreet interaction. This concept is akin to steganography, where an everyday mundane image contains a hidden message that can be extracted using a secret algorithm; however, steganography only applies to the message and does not encompass the user interaction. If it did, there might have been a concept coined as stegano-graphical user interfaces.

A discreet user interface could also help protect those in need and hinder “peepers and creepers.” Use cases could be messaging, banking, or general phone use in a public space. It could go even further, providing an outlet for those who are subject to coercive behavior or domestic abuse. At the same time, if an assailant or abuser found the discreet interface, this could put the user in danger. That is why this type of solution, if developed, may need to be rolled out by police or social services so that it could remain anonymous and safe.

A Simple Case Study: A Discreet News App

An example of a discreet user interface and use case could be the following: A female commuter, Jane, traveling home from work gets on board a busy train during peak hours. There are not many seats, so Jane stands. Along her 30-minute commute, two male commuters come on board and, given the limited space, encroach on Jane’s personal space. As Jane uses her smartphone, she becomes aware of the men’s presence behind her, making her feel vulnerable. They are watching everything she is interacting with, peeping and creeping.

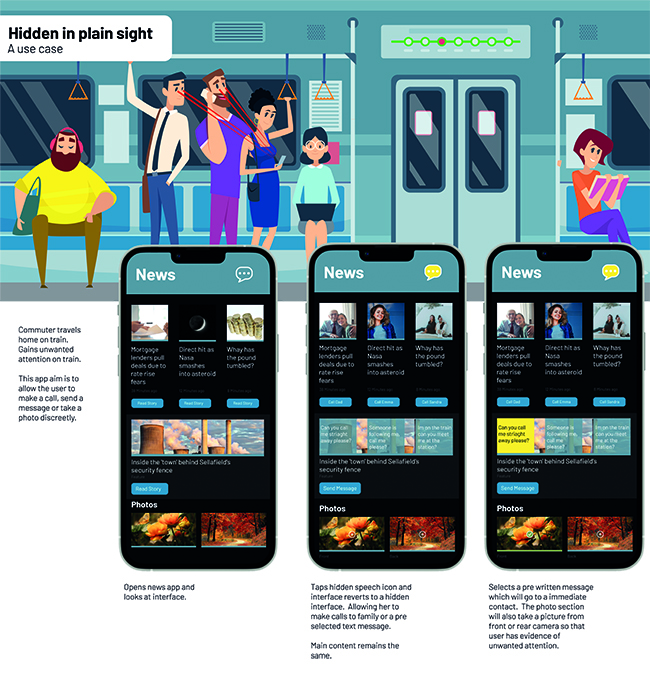

To stop this, she switches to her hidden interface, the “news” app (Figure 1), and reads a news item before interacting with a discreet feature. The feature allows Jane to discreetly, semiautomatically message a friend and alert her to meet her at the next station. As the train pulls into the station, Jane again uses the news app, where secret messages inform her of her friend’s confirmation and whereabouts.

The use case is twofold. In one sense, it’s a regular news app that will display a range of articles that can be read. But upon tapping an icon or button, the user interface can make calls and send prewritten text messages, all using the same content areas and buttons that already exist in the app.

Figure 1: This discreet user interface is called the news app. It displays news items, but by tapping icons and buttons, the user interface can send hidden communications, allowing the user to, for example, send prewritten messages, take a photograph, or make a call. Credit: onyxprj_art at vecteezy.com, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Conclusion

This article highlights the growing problem of “peepers and creepers,” unwanted attention by others while interacting with our digital devices. We considered a novel solution called discreet user interfaces, where an interface can look like it has a mundane utility but can have underlying functionality that allows it to discreetly perform other functions (e.g., hidden communication). We also presented a case study in the form of a discreet news app that showcases how a discreet user interface could work. We hope this article will be thought-provoking and will widen the conversation around discreet user interfaces and their use cases in interaction design and applications.

Endnotes

1. Haigh, L. Female travellers: a unique risk profile. ITIJ 230 (Mar. 2020); https://www.itij.com/latest/lo...

2. Dawson, A. So Generation Mute doesn’t like phone calls. Good. Who wants to talk, anyway? The Guardian. Nov. 7, 2017; https://www.theguardian.com/co...

3. HP creepers and peekers survey. HP Press Center. Sep. 25, 2019; https://press.hp.com/us/en/pre...

4. Kapur, A., Kapur, S., and Maes, P. Proc. of the 23rd International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces. ACM, New York, 2018, 43–53; https://doi.org/10.1145/317294...

5. Lee, J. et al. Itchy nose: Discreet gesture interaction using EOG sensors in smart eyewear. Proc. of the 2017 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers. ACM, New York, 2017, 94–97; https://doi.org/10.1145/312302...

6. Cascón, P.G., Matthies, D.J.C., Muthukumarana, S., and Nanayakkara, S. ChewIt: An intraoral interface for discreet interactions. Proc. of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, New York, 2019, Paper 326, 1–13; https://doi.org/10.1145/329060...

Posted in: on Thu, June 08, 2023 - 3:49:00

Kyle Boyd

View All Kyle Boyd's Posts

Raymond Bond

View All Raymond Bond's Posts

Maurice Mulvenna

View All Maurice Mulvenna's Posts

Karen Kirby

View All Karen Kirby's Posts

Susan Lagdon

View All Susan Lagdon's Posts

Becca Hume

View All Becca Hume's Posts

Post Comment

@نمایندگی بوتان در اندیشه (2023 07 12)

نمایندگی بوتان در اندیشه

https://www.faraztamir.com/andishe-butan/

@Angel17 (2024 06 04)

Your post is so informative. Keep sharing! chimney sweep augusta ga

@Vki Vhol (2024 06 26)

Na, az egy proba uzenet.

@shieffana (2024 08 20)

Research and use effective applications. Learn its applications. The information you update is really great to follow coreball. Detailed and engaging analysis to get an overview of the topic.

@Chesley Wilderman (2024 12 04)

What online channels uno online have you used to further expand your model market?

@Free AI Tools Free AI Tools (2024 12 16)

Thank you for this article, it is well written Remote Software JobsFree AI Tools

Latest Merch Deals Thank you for sharing.

@Charmaine lily (2025 03 11)

No need for boring quizzes. Love Pawsona turns self-discovery into a fun experience! You will answer interesting questions and bond with a cute animal character. From there, you will gain a better understanding of how you express love and connect with others. Try it now to find out who you are in the world of love!

@s (2025 04 17)

From 50kA to 300kA electrolysis lines, our modular copper refining systems adapt to various production scales. Trusted by 40+ smelting plants worldwide, our Electrolytic Copper Cleaning technology ensures 0.5μm surface smoothness for premium-grade copper cathodes.

@jannickz (2025 05 29)

Not saying you need to buy poe 2 currency to enjoy the game (SSFs, I see you), but for people who want to experiment with builds or skip the grind, it’s nice having a backup plan. Just make sure you’re being smart and using trusted sites.

@Level Devil (2025 06 08)

In this game world full of challenges and opportunities, Level Devil teaches us to bravely face difficulties, cherish friendship, and move forward with determination. Let’s embark on an adventurous journey with our little pig friends, exploring unknown territories and discovering inner strength and courage!

@Laurence Focke (2025 06 26)

This article on discreet user interfaces is eye-opening—designing apps that look mundane but serve hidden, protective functions is both clever and ethically nuanced. I especially loved the examples like AlterEgo or a “news” app doubling as a silent panic button—it shows real empathy for vulnerable users. Feels like the future of privacy-savvy UX is already here.

Also, if you’d like something light-hearted, check out this hidden gem: paaseieren kleurplaat

@Erasmus (2025 07 17)

The control mechanism in Crossy Road is very simple - just swipe left/right to move. However, as you progress deeper into crossy road, the obstacles become increasingly difficult, requiring players to have good reflexes and anticipation to overcome.

@cmeou88 (2025 08 26)

The term “peepers and creepers” describes unwelcome attention or invasive surveillance from others while they are using digital gadgets bitlife. This phenomena may cause unease, privacy issues, and a sense of ongoing surveillance.

@x2rowe (2025 09 25)

It’s so true, that feeling of vulnerability when traveling alone is something many can relate to. Your wife’s point about crowded trains is interesting; the illusion of safety can be deceptive. It’s a trade-off between physical and digital privacy. Makes me think about how much we rely on our phones for comfort. Almost like escaping into a different world, maybe even a virtual one like the one in Snow Rider 3D, haha, just to take your mind off things! It’s important to be aware and advocate for safer travel experiences for everyone.

@Clarkson (2025 09 26)

This is such an interesting concept! A business calendar calculator as a discreet interface could be very helpful. I appreciate the thought put into user safety and privacy in public spaces; it’s a growing concern in our digital age.