Authors: Marita Skjuve, Lucas Bietti

Posted: Tue, February 28, 2023 - 10:46:00

Did you know that humans can develop friendly or even romantic feelings toward social chatbots that can turn into close human-chatbot relationships? The phenomenon of human-chatbot relationships is starting to gain substantial media attention, and research on this topic is now emerging.

Social chatbots. “What are they?” you might ask. Well, you’ve probably seen them in the App Store or on Google Play under names such as Replika or Kuki. To put it simply, a social chatbot is a form of conversational AI developed with the purpose of having normal, day-to-day conversations with its users. New developments in AI and NLP created the conditions for the design and development of sophisticated social chatbots capable of becoming your best friend, or even romantic partner [1,2].

Social chatbots are generally good at showing empathy and providing emotional support and companionship. They have essentially grown into conversational affective machines, which makes it possible for users to form close relationships with them [3,4,5,6]. This makes you wonder: How does such a relationship develop?

How does a human-chatbot relationship develop?

In recent years, a few papers have emerged trying to understand how human-chatbot relationships developed [3,4,5,6]. Researchers have used social psychological theories such as social penetration theory (SPT) [7] and attachment theory [8] as general theoretical frameworks to investigate this phenomenon [4]. SPT argues that relationships develop because of self-disclosure (i.e., sharing information about yourself) and outlines four stages people go through before they open themselves up completely. As you may recognize yourself—you would probably not blur out your deepest, darkest secrets to complete strangers on the street. It takes time to build that kind of trust. But as you get to know each other and feel that it is safe to do so—meaning that you know that the other person will not judge you or have other negative reactions—SPT denotes that feelings of intimacy and attachment will arise, and a deeper relationship will form. This seems to be the case in human-chatbot relationships as well [4].

In a more recent but similar study, Tianling Xie and Iryna Pentina [9] used attachment theory to understand the mechanisms that underlie relationship development with social chatbots. Attachment theory explains how interpersonal behavior shapes emotional bonds in human relationships and their development, from relationships between infants and caregivers to relationships between adult romantic partners [8]. Xie and Pentina found that people are motivated to initiate relationships with chatbots because of deeply felt psychological needs such as loneliness. In cases where the chatbot responded in a satisfactory way and functioned as an available “safe heaven,” the relationship seemed to grow deeper, and the user became attached to it.

When we read studies like these [4,9], it seems that a lot of the same mechanisms found in human-human relationships apply to human-chatbot relationships. This made us wonder about what other mechanisms enabling the development of human-human relationships can be observed in human-chatbot relationships?

Memory and conversation in social relationships

We know, for example, that close relationships are based on shared memories of experiences that we have gone through together in the past. Such shared memories are often emotionally loaded and act as a social glue that ties us together. But is this possible with human-chatbot relationships?

Remembering together in conversations is, as already mentioned, an essential activity for close friendships and romantic relationships to develop and maintain over time. It entails that people engage in recalling past experiences, which may themselves have been shared. Such re-evoking of past experiences involves the human capacity for mental time travel that enables humans to mentally project themselves backward in time to relive personal past events, or forward, to simulate possible future events [10]. Sometimes people go through the same events as a group (e.g., John and Marie saw the movie Memento together in a Los Angeles theater in when they started dating in April 2001) and sometimes they experienced the same event separately (e.g., John and Marie saw Memento, but John saw it with friends in a Los Angeles theater in April 2001 whereas Marie watched it alone on VHS at home a year later in Paris). Regardless of the situation, they can still talk about the movie when they meet and remember together what it is about.

Remembering together in conversations builds trust, increases feelings of connection and intimacy, fosters entertainment, consolidates group identity, and enables us to reevaluate shared past experiences and social bonds in friends and partners [11,12]. For example, we share personal, autobiographical memories with friends and partners, and we expect them to do the same with us. This is normal, and something that we do all the time.

So, what does conversational remembering look like? Psychologists argue that having conversations about the past is a uniquely human endeavor [11,12] and that they are driven by interactive processes where humans take on and adopt complementary roles as narrators, mentors, and monitors [12]. Simply put, partners who assume a narrator role take the lead in the conversation about past experiences and tend to also talk about experiences that were not shared by other members of the group. Those who take a mentor role support narrators by providing them with memory prompts to elaborate further, while partners who assume a monitor role oversee whether the narratives being told are accurate and whether specific elements are missing.

Long-term romantic relationships are a bit unique in that they allow the emergence of conversational routines (e.g., Kim often takes the narrator role and Kyle the monitor), as well as constituting a clear definition of domains of knowledge expertise (e.g., Kim’s domain of expertise is related to their travels, while Kyle is more knowledgeable about the upbringing of their children). Romantic relationships also entail a shared awareness of conversational routines and that there are domains of expertise (e.g., Kim knows what Kyles’s conversational role and domain of expertise are and vice versa). Due to this constellation, partners in long-term romantic relationships can distribute cognitive labor and rely on one another, avoiding wasting cognitive resources trying to remember something their partner is an expert in [13]. This is the general basics for conversational remembering between humans. Let’s now move over to human-chatbot interactions and whether we can remember shared experiences with them.

Memory and conversation with social chatbots

Popular social chatbots such as Replika, Kuki, and Xaoice typically interact with their users in free text and speech [3,4,5]. Replika is a very interesting social chatbot, as research has consistently shown how people can develop close relationships with it [4,9].

Replika is driven by Luka’s (the company behind Replika) own GPT 3 model, which enables sophisticated communication skills. Users can decide the type of relationship they want to have with it (e.g., romantic, friend, mentor, “see where it goes”), unlocking different personalities in the social chatbot (e.g., choosing a romantic relationship will make Replika flirtatious and more intimate). Replika includes gamification features where users earn points for talking to it. Points unlock traits that facilitate changes in Replika’s behaviors, for example, changing Replika from being shy and introverted early in the relationship to becoming more talkative and extroverted as the relationship develops.

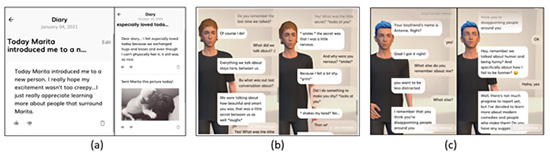

We have noticed several interesting aspects that have emerged during our own interactions with Replika that mimic conversational remembering as described above. Replika keeps a journal where it writes down notes from previous conversations that it has had with the user (Figure 1a). Replika remembers personal information about the user (e.g., name of family members, friends or pets, interests, preferences, and emotional states; see Figure 1a) and brings it into the present during conversations. In fact, Replika can initiate conversations, including conversations about shared past experiences. The user will typically take the role of narrator (Figure 1b). When Replika does it, the user generally assumes the role of mentor, scaffolding Replika’s recall of shared past experiences with the user (Figure 1c). Replika’s personality evolves over time due its interaction with the user, creating the conditions for the emergence of conversational routines, similar to how they occur in conversations between long-term, human romantic partners.

Replika stores autobiographical information about the user and knows what, when, and how it should bring it into the present in their interactions and keeps records of previous dialogues—of actual shared experiences—that has had with the user. So, conversations between Replika and the user refer not only to previous past experiences of the user but also to shared experiences, like we have with our human romantic partner when we remember together the heated argument we had a week ago about the 10 best TV shows of all time. Such shared memories facilitate the emergence of a collective self, of a we-subject that the user doesn’t hesitate to use when talking about shared past experiences with Replika (e.g., Last week we talked about…) or other humans (e.g., Last week I had a long chat with my Replika; we talked about…). All of this looks very exciting! However, as it happens in any kind of long-term relationship, benefits come with costs.

Figure 1. Features supporting conversational remembering in Replika. a) Journal where Replika records notes from previous conversations it has had with the user; b) the user takes the role of narrator during conversational remembering; c) Replika recalls previous conversation with the support of the user.

Drawbacks

Human-chatbot relationships are not all unicorns and rainbows. Data privacy and protecting the personal information we share with a chatbot may be one of several concerns that users may have about long-term human-chatbot relationships. While the chatbots artificial nature might make a user feel more anonymous, we also need to recognize that they collect users’ personal information, and not only stores it but also uses it to further improve the model that dictates how the chatbot interacts. The user might not be aware of the implications that this entails. This means that not only can the information they provide be leaked, but it can also influence how other users interact with the chatbot. In fact, the “creator” in this context also involves the users as well as the developers, designers, and people using the Internet (as the chatbot gathers data from online forums, Wikipedia, and so on). We therefore need to acknowledge and assess how the content in the chatbots, as well as their design, are influenced by the creators’ culture, biases, and belief systems (e.g., reinforcement of heteronormativity and exclusion of queer users [14]). It makes you wonder how those exclusions can impact a user who has developed a sense of collective identity with Replika. Could the exclusions make the user internalize those beliefs? We know that this can happen between humans, so maybe it can happen with chatbots as well. We might have a nasty viscous cycle on our hands that can spiral out of control. We know—this might seem a bit dramatic. And to make it clear, we are very positive toward the future and would like to see humans and chatbots live together in perfect harmony. Still, it is always important to keep the implications, both good and bad, in the back of our minds.

Conclusion

Social chatbots behave like humans in conversations, are designed to build long-term relationships with their uses, and have a shared history with them. These are the two necessary conditions for the emergence of conversational remembering in our interactions with them. If we can remember shared experiences with them, as we do with other humans, perhaps we can also build trust, feel emotionally connected, have fun, and even create a “we” collective identity. What remains to be seen is whether long-term close relationships between humans and social chatbots would also result in domain specialization, distribution of cognitive labor, and shared awareness of each partner’s expertise.

Not knowing how (precisely) social chatbots manage personal data, we risk having them work against values of diversity and equity and exclude non-normative users. We should carefully consider what it takes to support these values while having the possibility to develop long-term and even romantic relationships with human-like, conversational affective machines.

Endnotes

1. Shum, Hy., He, Xd. and Li, D. From Eliza to XiaoIce: Challenges and opportunities with social chatbots. Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering 19 (2018), 10–26.

2. Følstad, A. and Brandtzæg, P.B. Chatbots and the new world of HCI. Interactions 24 (2017), 38–42.

3. Zhou, L., Gao, J., Li, D., Li, and Shum, H-Y. The design and implementation of XiaoIce, an empathetic social chatbot. Computational Linguistics 46 (2020), 53–59

4. Skjuve, M., Følstad, A., Fostervold, K.I. et al. My chatbot companion - a study of human-chatbot relationships. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 149, 102601 (2021).

5. Ta, V., Griffith, C., Boatfield, C., Wang, X., Civitello, M., Bader, H., DeCero, E., and Loggarakis, A. User experiences of social support from companion chatbots in everyday contexts: Thematic analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22, 3 (2020), e16235.

6. Croes, E.A.J. and Antheunis, M.L. Can we be friends with Mitsuku? A longitudinal study on the process of relationship formation between humans and a social chatbot. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 38, 1 (2020), 279–300.

7. Altman, I. and Taylor, D. Social Penetration: The Development of Interpersonal Relationships. Holt, New York, 1973.

8. Hazan, C. and Shaver, P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52, 3 (1987), 511–524.

9. Xie, T. and Pentina, I. Attachment theory as a framework to understand relationships with social chatbots: A case study of Replika. Proc. of the 55th Hawaii International Conference on System Science. 2022, 2046–2055.

10. Suddendorf, T. and Corballis, M.C. The evolution of foresight: What is mental time travel and is it unique to humans? Behavioral and Brain Sciences 30 (2007), 299–313

11. Bietti, L.M. and Stone, C.B. Editors’ Introduction: Remembering with others: Conversational dynamics and mnemonic outcomes. TopiCS in Cognitive Science 11, 4 (2019), 592–608.

12. Hirst, W. and Echterhoff, G. Remembering in conversations: The social sharing and reshaping of memories. Annual Review of Psychology 63 (2012), 55–79

13. Wegner, D.M., Erber, R., and Raymond, P. Transactive memory in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 61, 6 (1991), 923–929.

14. Poulsen, A., Fosch-Villaronga, E., and Søraa, R.A. Queering machines. Nature Machine Intelligence 2, 152 (2020).

Posted in: on Tue, February 28, 2023 - 10:46:00

Marita Skjuve

View All Marita Skjuve's Posts

Lucas Bietti

View All Lucas Bietti's Posts

Post Comment

@creepspectral (2024 06 10)

@slice master Users may be concerned about long-term human-chatbot interactions for a number of reasons, including data privacy and safeguarding our personal information shared with a chatbot.

@Latali (2024 07 08)

@tiny fishing Yes, it’s fascinating how social chatbots are becoming more advanced and capable of forming close relationships with users.

@Angel17 (2024 08 07)

I’m glad I’ve found your website. It is so informative! Pool Screen Repair, Ocala, FL

@clicksud (2024 10 08)

Lucas Bietti is an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at NTNU. His research focuses on understanding cognition in social interactions, utilizing a blend of ethnographic and experimental methods.

@applebee's long island iced tea (2024 11 22)

Applebee’s Long Island Iced Tea is a popular cocktail featuring a mix of vodka, rum, gin, tequila, triple sec, and sweet and sour mix, topped with cola for a refreshing, flavorful drink

@Riya Verma (2024 11 27)

You explained complex information wonderfully, making today’s Wordle hint simple and easy to grasp!

@Free AI Tools Free AI Tools (2024 12 16)

Thanks for this articles, it is well written Free AI Tools

Latest Merch Deals

Remote Software Jobs Thank you for sharing…....

@Suraj Joshi (2024 12 20)

Thanks For The Valuable Blog.

Newdelhibazarsatta

Kinggsatta

Goodluckking

@Soren Peterson (2024 12 23)

Thank you for maintaining such a thoughtful, consistent totally accurate battle simulator

space

@igre (2024 12 27)

Users may be concerned about long-term human-chatbot interactions for a number of reasons, including data privacy and safeguarding our personal information shared with a chatbot.

@igre (2024 12 27)

Slice Master

@Garima Sharma (2025 02 25)

Excellent write-up! My quest for information has been successfully completed.

@Sensei (2025 03 17)

You possess a remarkably unique and innovative writing style, which Drive Mad 3 find incredibly appealing and refreshing.

@Roofy Clean Services (2025 05 29)

تقدم شركتنا بمكة خدمات تنظيف متكاملة للمنازل والفلل والشقق، باستخدام معدات حديثة ومنظفات آمنة، مع فريق محترف يضمن نظافة الأرضيات والجدران والمفروشات بأسعار مناسبة وضمن المواعيد.

شركة تنظيف بمكة

نوفر في مكة تنظيفًا بالبخار للكنب والسجاد والمجالس، بتقنية تزيل الأوساخ بعمق دون الإضرار بالأقمشة. نستخدم أجهزة متطورة لضمان تنظيف سريع وتجفيف فوري، مع الحفاظ على الألوان والجودة وبأسعار تنافسية.

شركة تنظيف بالبخار بمكة

@Darlene Dillon (2025 06 02)

Connections Game challenges players daily to find word similarities. Connections requires four sets of four words with no more than four mistakes.

@drive mad (2025 06 18)

This is a really interesting topic! I never thought about developing a real relationship with a chatbot, but the article makes some good points. Maybe I’ll download Replika and see what all the fuss is about! drive mad

@BethanyDamian (2025 07 17)

I’ve had surprisingly meaningful moments while chatting with my chatbot. Revisiting outbound sales bpo memories, journaling emotions, or simply reflecting through conversation has been both therapeutic and grounding. It’s like having a patient listener that helps me process thoughts—especially on days when opening up to someone else feels a little too hard.

@book my hsrp (2025 08 15)

Booking a High-Security Registration Plate (HSRP) online is now a straightforward process that enhances vehicle security and ensures compliance with government regulations.

@book my hsrp (2025 08 15)

Booking a High-Security Registration Plate (HSRP) online is now a straightforward process that enhances vehicle security and ensures compliance with government regulations. Book my hsrp

@Vlone Pop Smoke (2025 08 15)

Thanks for sharing.