Authors: David Fore

Posted: Tue, October 11, 2016 - 4:07:05

In politics, as in music, one person’s stairway to heaven is another’s highway to hell. Proof is in the polls: Americans across the political spectrum believe the country is headed in the wrong direction. And here’s the thing: Rather than dispute one another over the facts, we acknowledge only the facts that suit our present viewpoint and values.

Then there’s the fact that none of us believe in facts all the time.

As the unwritten rules of the 140-character news cycle render our political aspirations into a lurid muddle, our national conversation circles the drain into threats of bloodshed in the streets. Many are asking how we got here. The answer is this: our constitution, which was designed by—and for—people who hold opposing viewpoints about a common vision. The current election cycle demonstrates how this document still generates a governmental system that works pretty much as planned. It does so by satisfying most of Dieter Ram’s famous principles for timeless design most of the time. What’s more, I believe, this bodes well for the outcome of the current election. Read on...

So you want to frame a constitution...

The public has seized upon the vision of the American dream crashing into the bottom of a ravine, wheels-up, spinning without purpose. Rather than giving in to panic, however, I recommend taking a deep breath and listening closely. If you do, you might soon hear the dulcet chords and hip-hop beats of the century’s most successful Broadway musical, Hamilton, rising above the hubbub.

Design scrum, circa 1787. See: Cosmo

Here’s the scene: The Americans just vanquished the greatest military on the planet. The fate of the world’s newest nation now dances upon the knife-edge of history. The new leaders wear funky wigs while declaiming, cutting deals, and making eyes at one another’s wives. They are predicting the future by designing their best possible version of it.

Alexander Hamilton stars as the libertine Federalist who believes the Constitution should gather under its wing most of the bureaucratic and legal functions of a central government, complete with a standing army and a central bank. James Madison is the pedantic anti-Federalist who argues that rights and privileges must be reserved to individuals and states to guard against tyranny.

These two partisans hold opposing viewpoints, vendettas, and virtues. Their mutual disdain shines through every encounter and missive as they got busy framing a new form of government that balances each side against the other.

Back in the day, they called it framing. Today, we call it design thinking. Same difference.

In "Wicked Problems in Design Thinking," Richard Buchanan posits that intractable human problems can be addressed with the mindset, methods, and tools associated with the design profession. This means sustaining, developing, and integrating people “into broader ecological and cultural environments” by means of “shaping these environments when desirable and possible, or adapting to them when necessary.” Sounds a lot like the task of forming a more perfect union that establishes justice, ensures domestic tranquility, and all the rest.

Design is constructive idealism. It happens when designers set out to create coherence out of chaos by resolving tensions into a pleasing and functional whole that realizes a vision of the future.

Designers might balance content against whitespace, for instance, in order to resolve tensions in a layout that would otherwise interfere with comprehension. Designers are good at tricking-out flat displays of pixelated lights to deliver deeply immersive experiences. We craft compelling brands by employing the thinky as well as the heartfelt. And because the most resilient designs are systems-aware, we craft workflows and pattern libraries that institutionalize creativity while generating new efficiencies.

The Framers, for their part, were designing a system of governance that would have to balance different kinds of forces. The allure of power against the value of the status quo. The inherent sway of the elite versus the voice of the citizen. The efficiencies of a central government and the wisdom that can come with local knowledge. They resolved these and similar tensions with a high input/low output system designed for governance, and delineated by a written Constitution.

From concept to prototype to Version 1

The Framers knew their Constitution would be a perpetual work in progress. It would possess mechanisms for ensuring differences could always be sorted out, that no single political faction or individual could rule the day, and that changes to the structure of government—while inevitable with time—would have to survive the gauntlet before being realized.

The Framers arrived at this vision while struggling against the British, first as their colonial rulers then as military adversaries. They also had the benefit of a prototype constitution: the Articles of Confederation. Nobody much liked it when they drafted it and even fewer liked governing the country under its authority. It was a hot mess that nevertheless gave the Framers a felt sense of what would work and what would not. This prototype lent focus and urgency to the task of creating a successor design that would be more resilient and useful.

Hamilton and Madison represented just two ends of an exceedingly unruly spectrum of ageless ideals, momentary grievances, political calculations, and professional ambitions. Still, they were the ones who did the heavy lifting during the drafting process, while boldface names such as Jefferson, Franklin, Adams, and Washington kibitzed from the wings before rushing forward to take credit for the outcome. Sound familiar?

Also familiar might be the fact that the process took far longer and created much more strife than anybody had anticipated. Still, against these headwinds they shaped a Constitution (call it Version 1.0) that delineated the powers of three branches of government without including the explicit civil protections sought by Madison and the anti-Federalists.

Not wanting the perfect to be the enemy of the good, the Framers decided to push the personal-liberty features to the next release... assuming there would be a next release.

And there was. After shipping the halfbaked Constitution to the public, it was ratified.

Now Madison was free to dust off his list of thirty-nine amendments that would limit power through checks and balances of the government just constituted. This wish list was whittled down to the ten that comprise the Bill of Rights, ratified in 1791.

The resulting full-featured Constitution boasts plentiful examples of design thinking that address current and future tensions. It also contains florid prejudices, flaws, and quirks that hog-tie us to this day.

But still, it breathes.

First, the bug report

Let’s look at the current slow-motion spectacle over the refusal of Senate leaders to hold hearings on the President’s choice for filling a vacancy on the Supreme Court. It’s not that they refused to support the choice… they refused to consider his candidacy.

How could this be? It is owing to a failure of imagination on the part of the Framers, who did not anticipate that leaders would simply decide not to do their jobs. And so the Constitution is silent on how swiftly the Senate must confirm a presidential appointee, making it conceivable that this bug could lead to a court that withers away with each new vacancy.

And while this is unlikely—at some point even losers concede defeat if only to play another day—this is something that needs fixing if we want our third branch of government to function as constituted.

Other breakdowns are the result of sloppy code. Parts of the Constitution are so poorly written that the fundamental intent is obscured. The hazy lazy language of the Second Amendment’s serves as Exhibit A:

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

Umm, come again? Somebody must have been really rather drunk at the time that tongue twister was composed, which has since opened up a new divide between the two ends of the American spectrum.

Strategy is execution. See: sears.com

When in doubt, blame politics

More troubling to me are the results of two compromises that mar the original design. High on that list is the 3/5 compromise, which racialized citizenship and ensured that slaveholders would hold political sway for another century. This compromise ultimately sprang from a political consideration, in variance with the design, meant to ensure buy-in by Southern states. The prevailing view was that in the long run this kind of compromise was necessary if there was to be a long run for the country. The losing side held that a country built on subjugation was not worth constituting in the first place. Our bloody civil war and our current racial divides are good indicators that this was a near-fatal flaw in the Constitutional program, now fixed. Mostly.

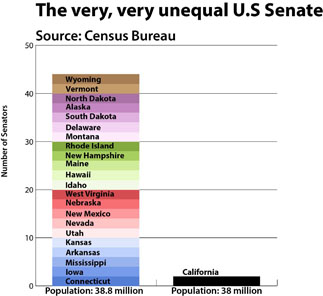

Another compromise in variance with the original design creates an ongoing disenfranchisement on a massive scale. Article 1 says that each state shall be represented by two senators, regardless of that state’s population. The result? Today’s California senators represent 19 million citizens each, while those Connecticut senators each represent fewer than 2 million people.

It’s important to note that this was a feature, not a bug. It was consciously introduced into the program in order to ensure that those representing smaller states would vote to support ratification.

And it works! We know that because every organization is perfectly designed to get the results it gets. This neart-autological axiom is attributed followers of Edwards Deming. In some ways the father of lean manufacturing, Deming showed how attention to outcomes sheds light on where design choices are made. In this case, small states have outsized influence, which keeps them in the game.

The Senate: undemocratic by design. See: Washington Post.

Still, not everything intended is desireable. Even Hamilton—notwithstanding his own skepticism about unbridled democracy—opposed this Senatorial scheme. Rather than dampening “the excesses of democracy,” which he saw as the greatest threat to our fledgling nation, this clause resolves nothing save for a short-term political problem that could have been addressed through means other than a fundamentally arbitrary scheme that would perpetually deform the will of the people.

Easy to use… but not too easy

Still, Hamilton got much of his design vision into the final product. The document boasts a wide range of process-related choke points, for instance, that permit plentiful consideration of ideas while ensuring few ever see the light of day.

Consider how a bill becomes a law. It must (almost always) pass through both the House and the Senate, then survive the possibility of a presidential veto, then avoid being struck down by the courts. By making it easy to strangle both bad bills and good ones in their cribs, this janky workflow is a hedge against Hamilton’s concern about an “excess of lawmaking.”

Does it succeed? Yes, if we judge it by the measure of fidelity between intent and outcome. Partisans shake their fists when their own legislation fails but they appreciate the cold comfort that comes from the knowledge that their friends across the aisle wind up getting stuck in the same mud as they do. (See Kahneman et al. on the subject of loss aversion.)

The killer app

If the Constitution has an indispensable feature, I cast my vote for the First Amendment. The Framers felt the same, so they provided it pride of place, designating it as the driving mechanism for all that follows. In so doing they confirm what we all know: that speech springs from core beliefs and passions whose untold varieties are impervious to governance anyway… so then why even try?

Equally important, by making it safe to air grievances about the government, this amendment guarantees that subsequent generations will enjoy the freedom to identify and resolve the tensions that arise in their lives, just as the Framers had in theirs. They also well understood the temptation of abandoning speech in favor of violence, a specter that always hovers above political conflict. Better to allow folks to vent so they don’t feel they need to act.

A success? Yes, if we evaluate the First Amendment by the clear fact of the matter that centuries later Americans do enjoy popping off quite a lot. Even if what we say is divisive and noxious. With a press [1] free to call B.S. on candidates, though, we have a good shot at exposing the charlatans, racists, and conmen among us. This amendment ensures that voters have the information they need to ensure that the keys to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue fall into the right hands. I, for one, am confident that we will.

What would Dieter do?

The Constitution is an imperfect blueprint created by manifestly imperfect men. In lasting 230 years, though, it has become history’s longest-surviving written national charter, doing so according to Ram’s principles of timeless design:

- It is durable, which also indicates a certain thoroughness.

- It is innovative, in that no country had established a democracy so constituted.

- It is useful, in that we depend upon it to this day.

- While not particularly aesthetic—and also often obtuse—the document manages to be unobtrusive in the way Ram means: it ensures our ability to express ourselves.

- It is for the most part honest in that it does what it sets out to do. Still, like other governments of its time, ours devalued and/or demeaned most inhabitants, including blacks, native Americans, women, and those without property. Still does, in many ways.

- By leaving many decisions to state governments and individual citizens, it has as little design as possible.

- Where the Constitution falls short, utterly, is Ram’s principle of environmental sustainability. And while this is forgivable given the historical context, we are now compelled to consider how to bend this instrument to the exigencies of our chance behind the wheel.

I admire Ram’s canonical principles, but I’ve always felt there is something missing. That’s magic.

Great design thrives in our hearts, and balances in our hands, just so. Great design is transcendent, and I have come to believe this is so owing to its ensoulment.

You sense the ensouled design because somehow it reflects your essence and furthers your goals, regardless of whether you understand how it does so.

In the case of our Constitution it is we, the people, who supply the magic. This is what the Framers intended. And so it is up to all of us to redeem the oft-broken promises of the past, and to realize a more inclusive, fair, and resilient vision of America, generation after generation.

Same as it ever was?

Endnote

1. Here, “the press” includes the Internet and its cousins. I’ve always wondered whether the First Amendment is chief among the reasons the United States has been a wellspring for the emergence of these sociotechnical mechanisms and their inherent potential for liberating speech for everyone everywhere. Further research anyone?

Posted in: on Tue, October 11, 2016 - 4:07:05

David Fore

View All David Fore's Posts

Post Comment

No Comments Found