Authors: Lauren Chapman Ruiz

Posted: Mon, April 22, 2013 - 11:44:47

I recently returned from a trip in which my team and I conducted a series of contextual inquiries with over 75 people on the topic of spinal cord injuries. We spoke with patients, caregivers, doctors, and nurses. It was one of the most humbling experiences of my life. My team’s ability to develop empathy and interview with honesty was critical, with strangers opening up to strangers. But what happens after all this research is completed? This is one of the hardest parts of design—translating needs into tangible direction, taking a leap from insight into making. A designer’s job is to turn research findings and client needs into something, which, ultimately, both serves the person’s needs and is a sustainable and profitable business investment.

Document, document, document

But let’s take a step back for a moment. You have just completed your research.

Naturally, it will first be synthesized and documented. But one of the worst behaviors I’ve found in organizations is the lack of proper documentation. Thousands of dollars are poured into research, and after it is conducted, it remains only in the heads of the researchers. The researchers become the gatekeepers to the insights. Often there is only a team discussion on the findings and actions are taken based on a light analysis. Due to the lack of proper documentation, the team doesn’t have the opportunity to see how the results could impact other current or future initiatives. And what happens when that researcher leaves? All of that information is gone.

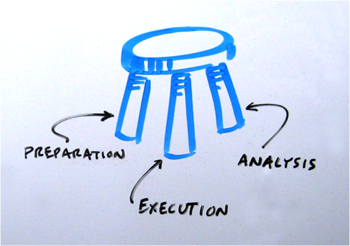

Analysis and documentation is critical. At MAYA Design, we like to say research is a 3-legged stool. You need the three legs of preparation, execution, and analysis—with equal effort and time for each. Without one, the stool will topple.

Turn key insights into stories

The process of analysis and documentation usually results in a set of key insights or lessons learned, personas, experience diagrams, labeling of breakdowns and opportunities, mapping of behavior and systems, and so on. Regardless of form, all of these deliverables tell a story about the research and what was discovered.

The form or type of deliverable can vary depending on the type of research and the purpose for it. I’ve noticed research is often used for three types of functions:

- Evaluative research of a concept, prototype, and/or a current product or service

- Need-finding research to derive completely new, innovative ideas for a business

- Need-finding research to discover where to go or how to improve upon a current products or services

Use generative activities to create design concepts

Once you’ve documented your research in the appropriate form, it’s time to make that “So what?” jump. You’ll need to do the hard thinking to translate the information into what it strategically means for your project or client. Often we take our findings and structure them into several generative activities to be completed in collaboration with our client. Examples of these activities might be developing statement starters to use in a creative matrix and then advancing the resulting ideas further with concept posters. These posters will illustrate a refined concept based on real needs. They might include the stakeholders and personas for which they were created, the needs which they fulfill, the details of the design and how the idea works, a development timeline, and/or challenges to producing the idea.

Build shared understanding

The purpose of these exercises is to collectively leap into what the research means and what next steps the client will need to take. It is important to do this as a group, creating a sense of shared ownership and gathering as many ideas as possible. Everyone will look at the research findings and interpret their meaning a little bit differently. Beware a single loud voice creating groupthink—instead, use activities that invite input from the whole team. This is how many ideas start to coalesce. And then it’s the designer’s job to begin shaping the vision.

Uncover transformational opportunities

For our project, the research uncovered opportunities to approach the problem in a holistic, systematic way rather than with a single-solution concept. If we hadn’t taken that analytical leap, if we had stayed buried in empathy and data, unable to synthesize our experiences critically, we would never have had the chance to actually improve the lives of others.

Lauren Chapman is a designer and researcher at MAYA Design in Pittsburgh, PA. She is also an adjunct faculty member at Carnegie Mellon University.

Posted in: on Mon, April 22, 2013 - 11:44:47

Lauren Chapman Ruiz

View All Lauren Chapman Ruiz's Posts

Post Comment

@quordle game (2025 01 22)

Great stuff! I’ll tell my friends about it and ask them to check it out. Thank you for sharing! When you have more time, go to: quordle

@doorsonline (2025 03 24)

It rightly emphasizes the importance of documentation, highlighting how lack of it can waste research efforts. Doors online game

@DDgames (2025 06 19)

Interesting read! It’s so true that good documentation is key to making research actually useful. I’ve seen so much research just disappear! Definitely something to think about.DDgames

@sammy (2025 07 27)

or “You Learned Stuff. Now What?” poses a crucial and often overlooked question: what do we do with all the learning we’ve learned? In an environment where access to knowledge is easier than ever, the real challenge isn’t learning, but activating that learning in meaningful ways.

The text invites us to move out of the passive mode of “knowledge consumption” and into a more proactive mode: applying, sharing, experimenting, questioning, and building.

price shoes basicos catalogo

Learning something has no real value if it doesn’t generate transformation—in our practices, our decisions, or how we collaborate with others.