Authors: Deborah Tatar

Posted: Tue, April 23, 2013 - 12:56:02

This is the fourth in a series of postings I’ve been writing about Ai Weiwei’s recently closed retrospective at the Hirshhorn, the significance of AI Weiwei’s art with respect to its commentary on the children who died in the Sichuan earthquake in 2008, and, implicitly, the relationship between design, representations, and society. This is, of course, a more art-centric view of design than usually found among a pragmatic ACM audience, but, arguably, this view is sometimes undervalued. Curse you, C.P. Snow!

The various pieces of art I’ve been describing occupy a thin space of commentary between the children’s deaths and the Chinese system, and raise other thoughts vis-à-vis non-Chinese, or at least American, customs, thoughts, practices, and technologies.

Ai Weiwei has a little book—not red—called Ai Weiweisms. In it, he says, and this was posted on the wall of his show:

"A name is the first and final marker of individual rights, one fixed part of the ever-changing human world. A name is the most basic characteristic of our human rights: no matter how poor or how rich, all living people have a name, and it is endowed with good wishes, the expectant blessings of kindness and virtue."

This is very beautiful.

But I wonder, is it true? Or, rather, in what ways do we make it be true or not?

I am not sure that Ai Weiwei always makes it be true. In the piece I described last time, Ai Weiwei used the dead children’s names to make an account of their deaths. He attempted to give the account himself that the Chinese government should give and will not. But, on my reading, an account is a tidying up, a normalizing, a distancing. An account is not an encounter; it is not grief; it is not confrontation. It is only part of what it needed. So, for me this piece was not really in the end about the children. It was not a memorial of them or their deaths but rather a testament to the failure of the Chinese system.

In America today, our own memorials are also mostly reduced to accounts. J.B. Jackson [1] describes how the changing notions of our relationship to death led away from pastoral encounters in such places as Mount Auburn cemetery in Cambridge or the plots out back we still have here in Southwestern Virginia, to the long bland arrays of, for example, an Arlington National Cemetery. There is a loss in such a reductive accounting, which is perhaps why so few people in my family are willing to be buried in American cemeteries. They would rather be scattered. They would rather contemplate glorious nothingness than impotent formalisms.

My own ancestors felt differently, and the Americans are mostly buried in the Jewish cemetery in Gloversville, New York. Gloversville was the thriving center of, yes, the glove trade in America from the time of Sir Henry Fonda (ancestor of Henry, Jane, and Peter) up until the miserable death of the industry documented by Richard Russo in books like Mohawk. (Richard Rubin, the glove expert in the O.J. Simpson trial, grew up catty-corner from my father in Gloversville.)

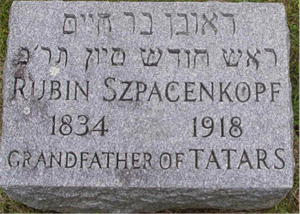

My uncle was buried in the orderly part of the Jewish cemetery two years ago, but there is also a more atavistic portion featuring the plunking down of bodies, reminiscent of the 11-fold piling of graves in the extant Jewish cemetery of Prague. Small, book-size, uneven stone markers are now illegible. I couldn’t find my grandmother’s brother, who died of tuberculosis in the 1910s, although he is almost certainly buried there. The plunking down of bodies is accompanied by memorable oddities. As you see in the picture below, by 1918 (or whenever the headstone was put in) there was enough prosperity to afford a substantial gravestone, but enough freedom of action to allow idiosyncracy. I’m not exactly sure why Ruben Szpacenkopf, who was my grandfather’s grandfather, is memorialized as the “Grandfather of TATARS” [2]. Everyone who could answer this question is dead. But I think I would find the inscription noteworthy even if my name were not Tatar. Clearly there is some kind of expectant blessing of kindness and virtue associated with this use of the name.

Both my mother and my father had connections to Gloversville, and my mother’s uncle Harry used to tell me that he remembered my grandfather’s grandfather (on my father’s side) often stopping by his house for a glass tea with my great-grandmother (on my mother’s side) on his way home from shul. Great-Uncle Harry’s point was that Rebbe Szpacenkopf was born before the Civil War, and that, through him (Harry), I was connected with that remote era by only two degrees of separation.

My mother’s parents are not buried in the Gloversville Jewish cemetery, for two reasons. The first is that they had a big fight with Great-Uncle Harry and his wife Cecile and moved their burial plots to Fort Lee, New Jersey. But why did they move their plots? One day, my grandmother explained “I don’t want Cecile looking down at me for all of eternity.” This did not correspond with any Jewish theology known to me. I said, “Grandma, do you feel that the spirits of dead people inhabit their graves until the apocalypse?” She muttered something incomprehensible. After a pause, I asked her whether she had ever seen “Our Town,” the play by Thornton Wilder, in which dead characters re-enact small town American life. She had no idea what I was talking about. But, just as she and my grandfather had moved to an apartment in New York City, they chose to be buried in an apartment-like mausoleum amidst strangers. It makes me happy to imagine, just as in life, their neighbors pounding on the walls between the coffins for them to turn the damn TV down.

In this digital age, I don’t know how I want to be remembered, by whom and for what purposes. However, I am sure of one thing. My father-in-law, dead for 25 years, is still “remembered” by AARP’s databases by the junk mail that we receive and, long after death, evidently moved with us from California to Virginia. At least, on this view, he’s not sitting on a gravestone in California talking with his neighbors about vitamins and Linus Pauling. But … yuch. To live on as a label? Neither AARP nor Ai Weiwei can bring back the dead by using their names.

I don’t want my name to live on in archives or for these purposes. Curiously, Rebbe Szpacenkopf’s memorial—the one in which there is no attempt to portray him as alive—vivifies a memory of people who are now themselves just memories. It seems the most attractive to me. But, failing that, when push comes to shove(l), I’ll probably prefer glorious nothingness to any of my choices.

Endnotes:

1. Jackson, J.B. (1997) From Monument to Place, an essay published in Landscape in Sight: Looking at America. New Haven: Yale University Press.

2. Rebbe Szpacenkopf was definitely not the grandfather of the nomadic Tatar people’s of the Crimea who are decedents of Genghis Kahn.

Posted in: on Tue, April 23, 2013 - 12:56:02

Deborah Tatar

View All Deborah Tatar's Posts

Post Comment

@Hal Tatar (2013 04 25)

Bravo from the author’s dad!

@Meg Dickey-Kurdziolek (2013 05 08)

Great post! Leaves a lot to think about!

It is interesting to me that in technology our names are treated like variables in programming. You can name your variable whatever you want - it is just used as a reference to get to the “meaning” or actual value. When we die, it is the equivalent of just deleting a user account. Just a bit flip. There are no technological tombstones or virtual ashes to scatter. Our “memories” don’t live on with the websites that care about us, they are just cleared. (Well, except for the AARP in your father-in-law’s case.)

@Pardha (2013 07 07)

Thanks Deborah for another interesting post. Before the computer age, I feel one had more control on when, where, and how one’s name shows up. Now with our names and personal information available for anyone to compile and post online things are different. Just try googling your own name and see!

@Nanci fisher (2014 04 12)

I am the great granddaughter of Sarah Gitel Szpacenkop. My grandfather was Jacob Tatar. We must be cousins. I do genaology and have a family tree. Write.

@Nanci Fisher (2014 07 22)

I am the great granddaughter oh Sarah Gittel Szpacenkopf . My grand father was Jacob Tatar. My mom is Miriam Tatar Pritkin. I am doing family geneology . Would love to connect with you.