Authors: Andrew Tzer-Yeu Chen

Posted: Fri, October 30, 2020 - 5:24:04

At this point, we are all familiar with Covid-19 and its impacts on ourselves, our communities, and our world. Responses to the disease have largely been led by local, national, and international public health agencies, who have activated their pandemic plans and opened the epidemiological toolkit of modeling, testing, isolation and movement restrictions, surveillance, and contact tracing. When it comes to contact tracing, it’s natural for people to see the tech-heavy world around them, then hear about the common manual process of human investigators and phone calls, and ask, “Why can’t technology help make this better?” But it’s not as simple as “add more technology”—the complex way in which users and societies interact with the technology has significant impacts on its effectiveness. When efforts are not well coordinated, leading to fragmentation in system design and user experience, the public health response can be negatively impacted. This article briefly covers the journey of how contact tracing registers and digital diaries evolved in New Zealand during the Covid-19 pandemic, how the lack of central coordination led to poor outcomes, and ultimately how this was improved.

Contact tracing registers and digital diaries?

Dr. Ayesha Verrall notes that “rapid case detection and contact tracing, combined with other basic public health measures, has over 90 percent efficacy against Covid-19 at the population level, making it as effective as many vaccines” [1]. Contact tracing involves identifying people who have been in contact with an infected person, and therefore who may have been unknowingly exposed to the infectious disease. By identifying the contacts and rapidly isolating and testing those individuals, the chains of transmission in the community are cut off, limiting the spread of the disease. Importantly, contact tracers need to find potential contacts who are unknown to the infected person, and can only do this by tracing the movement of the person to find others who may have overlapped in time and place.

With the pervasive nature of digital technologies, there has been a lot of discussion globally around digital contact tracing solutions, particularly around Bluetooth-enabled smartphone apps (including the Apple/Google protocol) and wearable devices [2,3,4]. Proponents of the technology offer the promise that these solutions can achieve better completeness (finding more contacts of cases, especially where the identities are not known to the case) and speed (finding contacts and testing/isolating them faster). However, in the absence of a validated, effective digital contact tracing solution initially, a number of governments opted for simpler, lower-tech methods of collecting data about people’s movements.

The contact tracing register (or visitor/customer check-in log) has been deployed around the world (Figure 1). Individuals are asked to provide their personal details at businesses and other places of interest, so that if a venue is identified as potential exposure site, then the register can be provided to contact tracers to quickly find people who were there at the relevant time. Digital diaries have also been introduced to help people keep track of their own movements to support their recollection if they get interviewed by a contact tracer—the distinction being that instead of the venue or the government holding the records, the individual themselves maintain and control their logs.

Figure 1. A pen-and-paper contact tracing book along with two QR codes for digital diaries in Wellington, New Zealand.

Too many solutions

In New Zealand, a strict Level 4 lockdown was implemented across the country on March 25. Most people (with the exception of essential workers) stayed at home, and the high level of compliance meant that within two weeks the number of active cases began to fall. After four weeks, on April 27, some restrictions (particularly around schools and takeaway food services) were eased at Level 3, and then most restrictions were lifted at Level 2 on May 13 (with the exception of physical distancing and gathering limits). As the country moved into Level 3, the government introduced a requirement under the Public Health Response Order for all businesses to maintain contact tracing registers. These registers required visitors and customers to provide their entry/exit times, name, address, and contact details to the business in case they are needed for contact tracing purposes. The government provided a template for businesses to print and use.

A number of criticisms were leveled at the pen-and-paper contact tracing registers that most businesses used initially. Customers had to provide their personal information on a piece of paper that was visible to all customers, creating a privacy risk. This led to real privacy breaches, such as a female customer being harassed by a male restaurant worker after he took her details from a contact tracing register. There were also some concerns about “dirty pen” risks (if everyone is using the same pen, could that become a vector for virus transmission?), usability (can people be bothered providing their details at every business they go to?), validity (could people provide false details?), and enforcement (can a business deny entry to someone who refuses to provide their details?).

Private software developers took the initiative to come up with better solutions. They reasoned that most people have smartphones (NZ has 80 to 85 percent smartphone penetration), and that using digital tools would mitigate or resolve some of the risks associated with pen-and-paper approaches. Within a week, there were over 30 tools available, almost all using QR codes, with a variety of system architectures and user flows. Some QR codes directed the user to a URL (thus requiring a mobile Internet connection); others required a specific standalone app to interpret the code. Some stored the data on a central server owned and controlled by the developer; others stored the data on the phone for the user’s reference only in a decentralized way (i.e., the “digital diary” approach). Some collected only a name and contact email address; others also asked for phone numbers and residential addresses —it was unclear what would be genuinely necessary for contact tracers to find people. Some tools were offered for free; others required businesses to pay a monthly fee, and two of the largest City Councils bulk purchased licenses of one product for businesses in their cities. Some providers had developed full privacy policies; others said that speed-to-deployment was more important. Unfortunately, there was duplication of effort, and many developers found themselves reinventing the wheel and then struggling under the burden of providing tech support for their products.

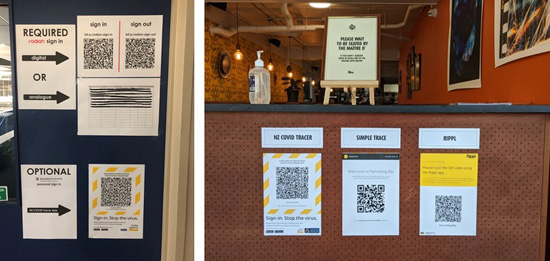

Figure 2. Photos of various QR codes from different providers in New Zealand, crowdsourced by the author from Twitter.

Almost every business soon adopted a QR code from one of these private providers, but with very little coordination or information around which systems were trustworthy or superior, chaos ensued. A lack of familiarity with how QR codes work among the public also led to significant confusion, with people getting frustrated when some QR codes worked and others didn’t. This was not helped by a number of the QR code posters using similar branding, such as the yellow diagonal stripes that were used in government messaging about Covid-19 (Figure 2)—some posters even using government logos to make their posters look more official. Most of the systems had centralized approaches, which also led to concerns about security and potential unauthorized reuse of data held by private corporations. Some businesses simply created Web forms and added clauses in their privacy policies that allowed them to reuse the collected data for marketing purposes, attracting a stern message from the privacy commissioner. However, an interesting counterargument was that since there were so many different tools, the data was fragmented between different providers and therefore no single company held too much data.

The undirected approach also meant that there was insufficient consideration for the needs of marginalized people. Posters were sometimes placed in positions that were inaccessible for disabled populations. Some businesses removed pen-and-paper registers entirely, making it impossible for participation by the digitally excluded—people without smartphones, or without the skills to effectively use the smartphone, or without expensive mobile Internet data. There was also some confusion about whether or not digital diary approaches (with the data staying on the device) complied with the regulatory requirement for businesses to maintain registers.

The government steps in

On May 20, a week into Level 2, the Ministry of Health launched the NZ COVID Tracer app. This was (and is) also a QR-code-based system with a “digital diary” approach. The app was accompanied by its own QR code standard, which contained a unique Global Location Number for each business, and therefore could be scanned without requiring an Internet connection. Data about check-ins (where people had been at what time) stayed on the device, and the user can choose to release that information to a human contact tracer if identified as a close contact of a known case. The app also allowed individuals to provide up-to-date contact details to the Ministry of Health, which would help contact tracers find them more quickly if necessary.

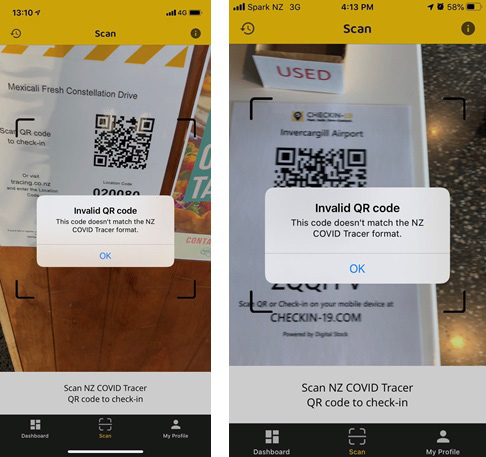

Unfortunately, QR codes were everywhere by this stage. Some businesses tried to provide multiple options (as shown in Figure 3) with clearer instructions. But this didn’t stop people from being confused about the proliferation of QR codes. The two loudest complaints about the government app were that 1) it wasn’t compatible with older devices (requiring at least Android 7.0 or iOS 12 at launch) and 2) the app didn’t recognize most of the QR codes that were available (Figure 4). The government app wasn’t designed to work with the other QR codes (which from a technical perspective might seem obvious, but for non-technical folks was bewildering). Displaying the government QR code was not mandatory, so many businesses didn’t even have it as an option.

Figure 3. Businesses attempting to provide clearer instructions on which QR codes to use, crowdsourced by the author from Twitter.

This fragmentation harmed the uptake of the government app because people felt that existing tools served the same purpose. Within a week of launch, about 380,000 users were registered, equivalent to approximately 10 percent of the adult population of four million people. Registrations plateaued, and a month later sat around 570,000. Meanwhile, the number of QR codes being scanned each day was counted through Web analytics events, slowly ramping up initially as businesses started printing and displaying government QR codes, settling around 50,000 scans per day in early June. Given the size of the population, this was clearly not enough activity to give us confidence that the data from the app would be useful in the event of a further outbreak. However, the government app was the only one that reported statistics about usage, so we don’t have data about how widely other tools might have been used.

Figure 4. Screenshots from users complaining that the NZ COVID Tracer app wasn’t recognizing the QR code, when they were in fact scanning QR codes from other providers, crowdsourced by the author from Twitter.

It turned out that the government app had actually been in development (with a private sector partner) for at least a month. The specific reasons for why the app was released late have not been made clear yet, although it should be noted that the government has a higher onus to “do things correctly” and needed to prepare a full privacy impact assessment, undergo an independent security audit, have the app checked by the government cybersecurity bureau, and complete other steps that weren’t required for private developers.

By July, it appeared that we had the pandemic under control. New Zealand experienced 102 days in a row without any community cases of Covid-19 detected. The Prime Minister moved the country to Level 1, lifting almost all restrictions except for border controls. Most people became complacent around the risks of Covid-19, with daily scan counts dropping to 10,000 in early July. There were even reports that some businesses were taking their posters down because they felt the QR codes were no longer necessary.

An improvement to the app in June introduced exposure notification functionality. Contact tracers could identify and securely broadcast a place and time where an active case had been, and then the app would check that against the check-in logs on the device and notify the user if an overlap was found. In late July, a further improvement was made to allow users to add manual entries, mostly to account for venues that did not have a government QR code. However, while there were minor upticks in registration and usage after these releases, the activity level still remained very low.

Consolidation is the solution

On August 11, the Prime Minister announced that four cases of community transmission had been found in Auckland (the largest city in New Zealand). There were no links to overseas travel, so it was highly likely that there were other undetected cases in the community. Given the recent experiences of places like Victoria, Australia, where second waves have grown quickly, the government implemented a second lockdown, with stricter movement restrictions in Auckland. In the next day, they also announced that displaying a NZ COVID Tracer QR code in a prominent place would become mandatory for all businesses by the following week. It would still be optional for individuals to scan, but at least the codes had to be available for people to scan if they wanted to. This decision wasn’t without precedent—Singapore required their SafeEntry QR codes to be displayed at all businesses in May.

This announcement caused three things to happen over the following week. First, the private developers with the most prevalent QR codes agreed that consolidation was necessary, and advised their customers to switch to the government QR code. Second, businesses largely complied, with the number of government QR codes increasing four times over the subsequent two weeks (from approximately 87,000 to 324,000). Third, the presence of the disease in the community in New Zealand and the accompanying lockdown elevated the seriousness of the situation, and more people began to scan the NZ COVID Tracer QR codes.

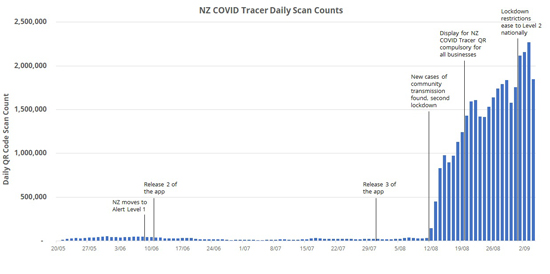

Figure 5. Daily scan counts from the NZ COVID Tracer app, overlaid with significant events. Data sourced from the NZ Ministry of Health.

The number of daily scans shot up, from approximately 30,000 per day before the second wave to over two million per day (Figure 5). The number of registered users also increased, from 640,000 before the second wave to just over two million users (approximately 50 percent of the adult population, although duplicate registrations are not accounted for) as of September 4. While the change in context was a significant driver for shifting user behaviors, moving away from the fragmented system clearly helped increase participation in the system too.

Unfortunately, this increase in participation came too late to be of significant help for the second wave. In the event of an outbreak, contact tracers need at least 14 days of movement logs for infected cases in order to help find close contacts. While the government did use the app to publish six exposure notifications, and some close contacts were found faster because they had updated their contact details, it seems that ultimately the app is yet to find significant numbers of close contacts or new cases. As New Zealand now comes out of its second lockdown, we can only hope that the current level of participation continues to grow for NZ COVID Tracer, and is sustained long enough to help defend against a potential third wave of cases in New Zealand.

Leadership and communication

When a global pandemic catches the world by surprise, a strong response is needed to contain, mitigate, and recover from its impacts. The public expects government to play a leading role in coordinating this response, but many individuals also want to do something to contribute. While people are to be lauded for utilizing their skills to support the broader community, undirected efforts can lead to confusion, duplication of effort, and ultimately harm the overall response. This is not the fault of the individuals—the responsibility lies with the public health agencies to make good use of the available resources and to clearly communicate with people about what is and isn’t needed. Normally, competition between private entities in the open market might be desirable to drive innovation, but in a pandemic, we really need something that just works and supports progress on public health outcomes.

In a country that has had strong communication with the public overall, the confusion around contact tracing registers has been an unfortunate blemish for New Zealand. This case study shows that fragmentation can lead to disparate and negative user experiences, which can harm trust in the system and lead to low participation. In the context of a global pandemic, trust is one of the things we need the most for an effective response.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the local Twitter community for contributing their images of QR codes to the dataset, and for engaging on digital contact tracing during the COVID-19 pandemic. The author also acknowledges members of Koi Tū: The Centre for Informed Futures for discussions around the use of technology for contact tracing.

Endnotes

1. Verrall, A. Rapid audit of contact tracing for Covid-19 in New Zealand. New Zealand Ministry of Health. Apr. 20, 2020; https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/rapid-audit-contact-tracing-covid-19-new-zealand

2. Wilson, A.M. et al. Quantifying SARS-CoV-2 infection risk within the Apple/Google exposure notification framework to inform quarantine recommendations. medRxiv. Jul. 19, 2020; https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.17.20156539v1

3. Asher, S. Coronavirus: Why Singapore turned to wearable contact-tracing tech. .Jul. 4, 2020; https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-53146360

4. Alkhatib, A. We need to talk about digital contact tracing. Interactions 27, 4 (Jul.–Aug 2020), 84; http://interactions.acm.org/archive/view/july-august-2020/we-need-to-talk-about-digital-contact-tracing

Posted in: Covid-19 on Fri, October 30, 2020 - 5:24:04

Andrew Tzer-Yeu Chen

View All Andrew Tzer-Yeu Chen's Posts

Post Comment

@drywall repair (2024 05 14)

Customers had to provide their personal information on a piece of paper that was visible to all customers, creating a privacy risk.

Fort Worth Drywall Contractor Services Fort Worth

@gi revive (2024 11 04)

Dr. Ayesha Verrall’s insight on contact tracing efficacy being comparable to vaccines is eye-opening! It’s impressive how different methods, like digital diaries, were developed to fill gaps in the contact tracing process. The discussion on fragmentation and the need for coordinated systems really resonates, as it’s a key factor in improving public health responses.

@Anna (2024 11 04)

I found it really helpful to read about the different approaches New Zealand took to refine its contact tracing efforts. The balance between technology and manual processes is indeed complex. I especially appreciate the explanation of digital diaries and how they empower individuals to track their movements independently. Great post!

gi revive

@Raquel (2024 11 08)

This is such a thorough and informative post! It’s amazing to see how quickly New Zealand adapted, from relying on pen-and-paper records to adopting QR codes and digital diaries. The insights into privacy concerns and the impact on marginalized communities are eye-opening. It reminds us that technology, while helpful, isn’t always accessible to everyone. How can governments better consider accessibility in future digital health initiatives?

Regards,

nutritionist london

@Guest (2025 03 20)

miside is the most addictive and immersive game I’ve played in years. The gameplay is simply outstanding!

@joe (2025 05 20)

Dr. Ayesha Verrall’s insight on contact tracing efficacy being comparable to vaccines is eye-opening! It’s impressive how different methods, like digital diaries, were developed to fill gaps in the contact tracing process. The discussion on fragmentation and the need for coordinated systems really resonates, as it’s a key factor in improving public health responses.

wacky flip

blacksmith master

@jackcarter (2025 07 18)

I witnessed how fragmentation between local and national health systems delayed critical decisions during Covid-19. Inconsistent messaging, data silos, and lack of coordination post acute facility made public trust harder to maintain. Strengthening collaboration, sharing real-time data, and aligning strategies are essential to ensure a faster, more unified response in future health crises.