How was it made? TypeCase

Issue: XXVI.5 September-October 2019Page: 14

Digital Citation

Authors:

Dougie Mann

Describe what you made. I made a physical keyboard for today's modern smartphones, attempting to bring back tactility to texting. Think Blackberry, or an old Nokia, where you could type very quickly on a physical board and without looking at the screen. I have tried to embody that nostalgic interaction and reinvent how we type on our phones and computers.

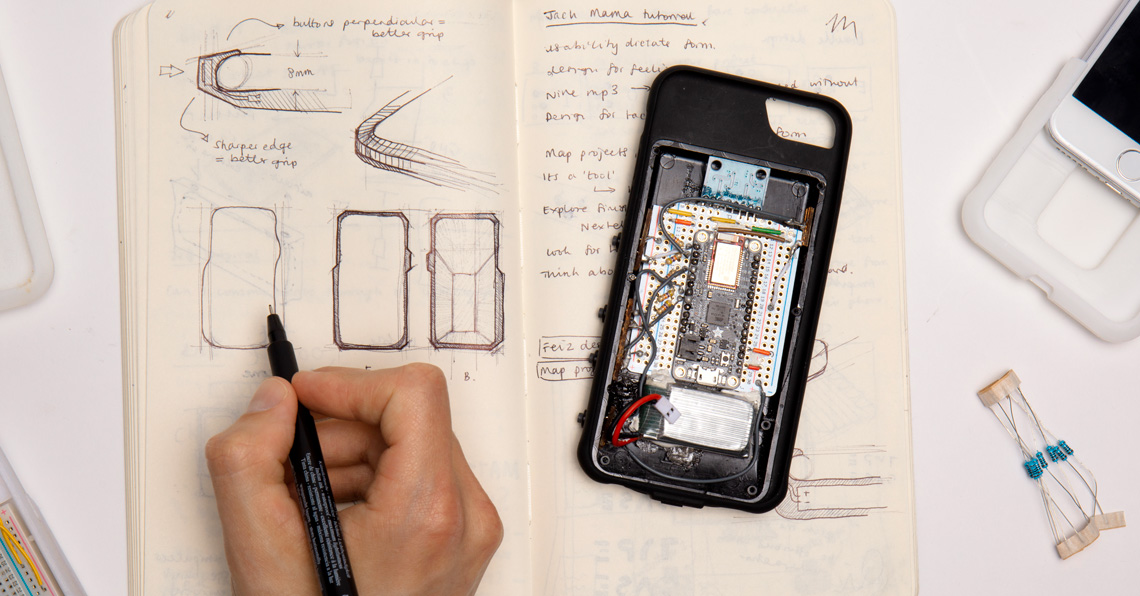

TypeCase is a smartphone accessory that has a button for each finger, placed around the edge of the phone. By pressing combinations or "chords" of buttons, you can very quickly type out words and sentences. The device is actually very simple, consisting of a 3D-printed resin phone case exterior with an Adafruit Feather microprocessor inside to control what the buttons do. It emulates a Bluetooth keyboard, so you can connect it to any device immediately and start controlling it without any apps or drivers.

|

This was the very first smartphone keyboard prototype, consisting of five buttons hooked up to the Bluetooth module. A mockup of a phone screen was used to help one's imagination in context. |

Briefly describe the process of how this was made. The process was extremely experimental to start, and became more refined over time as both the real problem and solution started to materialize. The question I began with was: How can we destigmatize with disability design? After some unusual social experiments and technological developments such as a keyboard glove and a pressure board, I began to focus on creating a device that was more realistic and forward-thinking. Integrating the technology into a smartphone meant that it had a pragmatic place in today's world.

|

Two prototypes were manufactured and refined for user testing. They were fully functional, allowing control of a computer mouse as well as Bluetooth keyboard use. |

What for you is the most important/interesting thing about what you made? For me it was the idea that I created my own "language." While it is still based on existing syntax, the communicative tool is novel—particularly with the idea that when learned, someone can actually read through haptics. With enough practice, this could be the first tactile language, with a place in AR, VR, or future technologies.

|

A development of experiments and prototypes that resulted in TypeCase (lower right-hand corner). |

What will you repeat in another project that you did well in this project? The breadth and intensity of analysis of each prototype really pushed the concept forward. My very first computer test with an amputee was extremely insightful. The prototype was buggy and cumbersome, but the exercise pointed out some obvious flaws, such as poor hand anthropometrics. This process allowed me to quickly test theories and technologies, and understand the best way to solve the problem at hand (pun intended).

What is one thing about making this that you would like to share with other makers? The most important thing is to correctly frame the problem. I didn't begin this project wanting to create a keyboard for the blind; I began with a much higher-level thematic question on disability design, and let the problem and solution come naturally. I had the luxury to explore some concepts—one being the balance of form and function in wheelchair design. The study I conducted resulted in an interesting finding that showed how the handles on the back of wheelchairs are quite often more stigmatizing than they are helpful, as they imply the user is incapable of their own mobility. Trusting in this loose design process is scary—for engineers more so than for designers—but it is an invaluable skill to have.

|

A hero image render of TypeCase, hinting at the subtle interior of the phone case, showing that it's not your average smartphone accessory. |

Dougie Mann, Imperial College London and The Royal College of Art, [email protected]

Copyright held by author

The Digital Library is published by the Association for Computing Machinery. Copyright © 2019 ACM, Inc.